In an era in which scientists are working to resurrect woolly mammoths and reverse-engineer birds into theropod dinosaurs, humanity is confronted with profound ethical and practical questions surrounding de-extinction. These include what it truly means for a species to be extinct, whether we should bring a species back simply because it is possible, and whether a biologically revived species that has lost its original ecosystem or culture is still the same species.

These are also among the many thought-provoking questions explored in Alan Dean Foster's science fiction novel Relic, in which a seemingly functionally extinct Homo sapiens is the species chosen for revival by a supposedly more advanced race. The book uses this fictional premise to present us with a series of philosophical issues around de-extinction, which it proceeds to ponder with depth and nuance.

Or at least, it does so until about midway into its plot, when it pivots from its philosophical musings to a more conventional narrative centered on territorial disputes and interspecies conflicts. From that point on, what began as a thoughtful meditation on a trove of weighty issues devolves into a routine story with familiar tropes, and even some plot developments that undermine the earlier discussions about de-extinction. All of this makes for a frustratingly lopsided reading experience: a great beginning, followed by a bafflingly uninspired letdown of a conclusion.

Relic is set in a far future in which the human population has been decimated by a bioweapon of humanity's own making called the Aura Malignance. Our main character, an elderly man named Ruslan, is from the planet Seraboth, the last human-colonized world to succumb to the plague. Some years ago, he was discovered and rescued from the brink of death by an alien race known as the Myssari. When they found him, he had long been aimlessly wandering Seraboth in search of others of his kind. He had become so disconnected from his own humanity that he couldn't even remember his full name–only that Ruslan was one part of it.

Since bringing Ruslan into their fold, the Myssari have sheltered him on their homeworld and used their advanced science to extend his life and make his body amenable to their environment. Ruslan is grateful for their care and has done his best to integrate into their culture, picking up their language and customs and forming friendships with a number of his Myssari companions. Humankind, having thus far been confined to the "quiet side of the galaxy," had never before encountered an extraterrestrial race–an irony not lost on Ruslan, who often reflects on his distinction as both the first and last human to do so.

The Myssari are highly intelligent, three-sexed beings–with a physiology also built around threes, including three of each digit and triangular, gimbal-mounted heads–who are known for their courteousness, as well as their cold scientific curiosity. They have an ambitious plan to pull humankind back from near extinction by way of clones derived from Ruslan's genetic material.

Ruslan is adamantly against this project, believing the resulting humans would be only hollow imitations lacking the essence and culture of the original species. Though he knows his opposition is futile–the Myssari will proceed regardless of his feelings–his resentment is building. Finally, frustrated by the disconnect between their cloying politeness and the cruelty of their actions, he snaps at one of the Myssari to "stop being so damn nice."

The Myssari seem to be motivated by a combination of curiosity and a rigid, almost doctrinal commitment to species preservation; as one of them reminds Ruslan, "You know that we believe that the preservation of any species, especially of an intelligent one, far outweighs the personal preferences of any one individual." In short, theirs is a philosophy that values species survival as an abstract principle over individual autonomy or long-term ecological consequences.

In addition to using Ruslan's genetic material against his will, the Myssari expect him to serve as a cultural architect for the new humanity, for they seek not only to revive the human species, but to imbue it with the values, traditions and social structures it once possessed. "[W]e need you to instruct those we bring forth in how to be human," one of the alien scientists tells Ruslan, as if modern-day birds made to resemble dinosaurs could be taught the ways of an epoch now tens of millions of years vanished.

The folly that a species' cultural identity and memory can simply be restored with the flip of a switch is later driven home by the unsettling metaphor of cryogenically preserved humans being reanimated in a brain-dead state. This happens when a group of Myssari scientists, accompanied by Ruslan as an advisor, travels to another planet and discovers a facility containing frozen human bodies. These individuals underwent cryogenesis in the hope that future humans would find both a cure for the plague wiping out humanity and a way to bring frozen bodies back to life. The Myssari succeed in reviving their breathing and other involuntary functions, but not their consciousness.

We find ourselves reflecting on how, with the death of a species or any of its individual members, something vital is always lost. Indeed, we have fossils of dinosaur bones, but they're long devoid of viable DNA with which to clone new dinosaurs. Science, for all the ruthless efficiency with which it has thus far aided humanity's attempted conquest of nature, has its limits.

There's also a journey to another world to investigate a reported sighting of another living human besides Ruslan, which introduces the rather intriguing theme of humankind having entered into a cryptid-like status. Much as today's scientific mainstream tends to dismiss alleged sightings of Bigfoot or the Loch Ness Monster, so, too, is there skepticism around the legitimacy of these reports of a human sighting.

This is roughly where the novel begins to go astray. Without giving too much away, I'll just say that Ruslan turns out not be the last living human after all–not by a long shot–and that this revelation serves to nullify the stakes that were established at the story's outset. The existence of other living humans adds no new depth or complexity to the story; rather, it feels like a mere contrivance and a mockery of our earlier emotional investment in Ruslan's plight as the supposed last human. The tension around the question of humanity's survival is suddenly completely deflated, and all those existential questions lose all relevance.

The interspecies conflicts arise with the introduction of a second extraterrestrial species that feuds with the Myssari over the resettlement of Earth with newfound humans. These other aliens, the Vrizan, are interesting and just as well developed as the Myssari, but the plot hardly does them justice.

That good, early part of the novel, it must be said, has many virtues beyond its weighty themes. Among its other strengths are excellent world-building, evocative descriptions of alien landscapes and ecologies, and Foster's characteristic dry, droll wit and commitment to verisimilitude. If only they were matched by the story's execution during its latter stretch.

*******

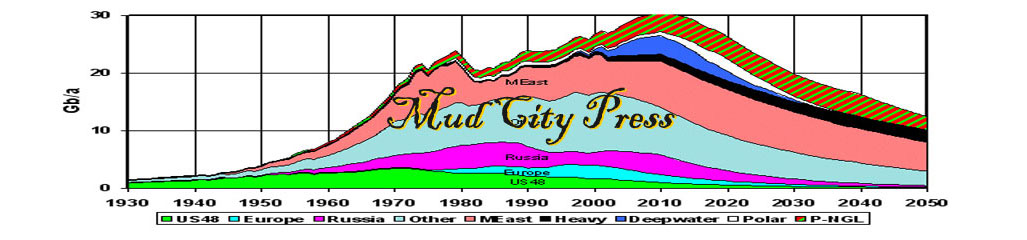

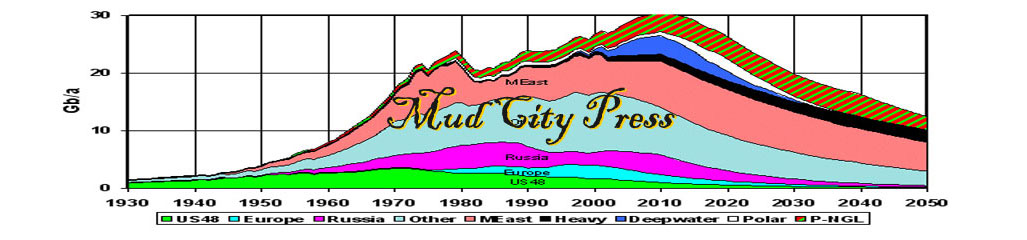

If you enjoyed this review, try Prairie Fire. Imagine Tom Clancy writing a multilayered thriller about peak oil.