5/21/2022

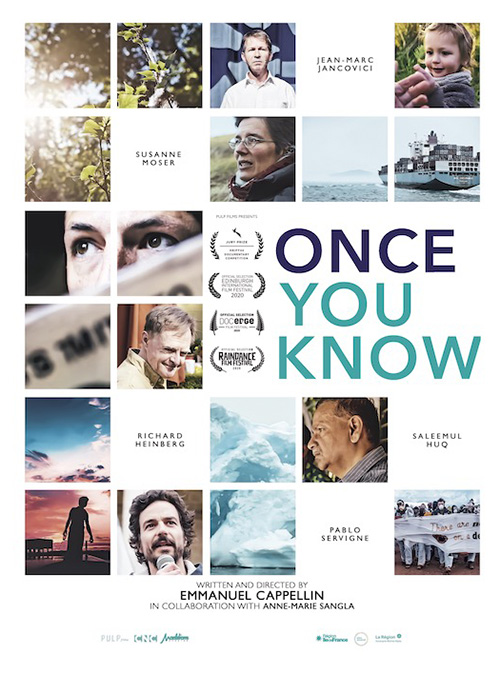

Emmanuel Cappellin is a fine filmmaker, an eager student of ecology and a fervent environmental activist. Once You Know is his first feature-length documentary, and it's a stunning debut. Part personal memoir and part big-picture look at today's environmentally threatened world, it asks two of the most vital yet fraught questions of our time: What does it mean to truly understand the reality of humankind's ecological predicament, and what should you do with that understanding once you possess it? The film is captivating in the way it goes about addressing these questions, which involves beautiful cinematography, wonderfully written narration and powerful visual storytelling.

It opens with a serene montage of nature footage and a voiceover in which Cappellin reminisces about his early childhood spent in awe of the natural world. Cappellin then recounts how, as an Earth sciences undergraduate, he first became aware of the enormity of the anthropogenic threats facing Earth's biosphere. He goes on to describe his subsequent 10-year globetrotting campaign to "save the world," an adventure that saw him plant trees in the equatorial rainforest, join the zero-waste movement and interview prominent climate scientists for political films. But the tone takes a depressing turn when Cappellin reveals that these efforts only brought renewed despair, for none of them succeeded in slowing down our civilization's headlong rush toward disaster. Demoralized, Cappellin resorted to what he calls "the mandatory spiritual journey eastward."

Ironically, it was not this spiritual journey itself, but rather the physical one that bore him to it, that revitalized Cappellin. He was traveling across the ocean on a container ship (having given up flying) when he found himself overcome by a mixture of nausea and morbid fascination at the sight of thousands of containers filled with consumer goods. The film brilliantly reenacts Cappellin's ordeal; his emotions are perfectly conveyed in a scene that intercuts stumbling point-of-view walking shots inside the ship's sterile metal corridors with increasingly frantic footage of industrial-era atrocities like atom bombs detonating, icebergs calving and animal carcasses dangling from factory conveyor belts.

Cappellin's disorientation soon gave way to realization. He had long ago read the Club of Rome's groundbreaking 1972 report The Limits to Growth, with its scenarios of global catastrophe if industrial society failed to heed the constraints imposed on it by the limited resources of our finite world. However, something about the sight of all those shipping containers made that report's message click with him in a way that it never had before. So he revisited Limits and noted that its disastrous business-as-usual scenario lined up remarkably well with the real-world course of events over the past several decades. Since that scenario saw both the global economy and the human population crashing precipitously by the mid-21st century, that's what Cappellin came to believe we were in for over the next few decades.

Thus began a new calling for Cappellin. He resolved to use his filmmaking skills to raise awareness about our ongoing civilizational decline and to promote individual and collective resilience in the face of it. In 2012, he started writing this documentary. He also began forging connections with experts in fields such as climate change adaptation, fossil fuel depletion and "collapsology," three of whom went on to have starring roles in the film. Their interactions with Cappellin are relaxed and personal; they talk with him in their homes, cars and other natural environments rather than in formal studio-type settings. While they spend a fair amount of time discussing their research into the larger issues, Cappellin does a great job of getting them to open up about their private fears, joys and hopes for the future as well. The end result feels like a meeting of hearts and minds—as well as journeys—among kindred spirits.

The scenes featuring author and Post Carbon Institute Senior Fellow Richard Heinberg are a case in point. Heinberg is an avid violinist, and the film captures him at home soulfully playing away on his instrument. As the camera pans through and around his and his wife's modest, eco-friendly home in Santa Rosa, California, Heinberg begins to tell his story. He says he originally wanted to make a career of his music and other artistic pursuits, but that his goals changed dramatically when he first read Limits as a young man. "When I read the book," he recalls, "suddenly all the other things I was doing–music and art–just seemed to recede in importance." His new passion became educating others on the problems facing humanity as a result of its reckless exploitation of fossil fuels.

Over the past two decades, Heinberg has established himself as one of the world's preeminent authorities on this topic. He has written many excellent books on it and has regularly appeared in documentaries and on the news to explain it to the public. Cappellin wonders what it's been like for Heinberg to have to live with his acute knowledge of such a dour subject for all these years, so he comes on camera to ask him about it. During an intimate conversation around the dining room table, the energy expert admits he loses a great deal of sleep over this issue. Asked whether it's the reason why he and his wife, Janet, have chosen not to have children, he confirms that it is.

We then follow Heinberg to Athens, Greece, for a conference where he's presenting. His talk is rousing; and back at the hotel, there's some equally lively discussion between him and Cappellin. They talk about how Greece's handling of the economic crisis in which it's now deeply mired (this is the summer of 2015) stands to set an important example for the rest of the world.

The film's second main expert is climate scientist Saleemul Huq, who serves as director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development. Huq is a leading figure in the emerging science of climate adaptation. He's also an ardent advocate for countries that find themselves suffering the most from climate change despite contributing the least to it. One of these countries is his native Bangladesh, whose coastal belt is rapidly sinking underwater due to climate change-induced sea-level rise. As we watch Huq stare broodingly out over the beleaguered Bangladeshi coast, Cappellin gives this summation of the man: "I sense a man caught between two worlds, caught between anger and determination. Saleemul is already part of those suffering the consequences. He's also part of those who have the luxury of anticipating."

Cappellin accompanies Huq to Paris for the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 21), and then to one of the many Bangladeshi villages ravaged by climate change. At the conference, we watch Huq speak and take part in the negotiations, arguing passionately for the contentious "loss and damage" clause that would oblige high-carbon-emitting countries to compensate those countries that emit little but suffer greatly from climate impacts. In Bangladesh, we visit a village whose way of life has been turned upside down by the salinization of formerly freshwater sources due to seawater intrusion. We see up close how this village has valiantly adapted by reinventing itself from a rice farming community into a saltwater fishing community. We're as impressed as Cappellin is by the villagers' pluck and perseverance.

Our final interview subject is Susanne Moser, a geographer and expert with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) who specializes in climate change adaptation and communication. It is while following Moser that the film is at its most metaphysical and inventive in its choice of settings. We first meet her at twilight on a windswept beach where she tranquilly muses to Cappellin while gazing out at the ocean. She tells him humanity has been presented with an extraordinary opportunity. Just as individual people become more alive when facing the prospect of their own mortality, so too, she says, do we as a species have a chance to do the same with regard to climate change.

We then find Moser giving a fascinating soliloquy as she browses a library in search of answers to the crises of our time. The lighting is stark among the towering stacks, adding to the sense of deep mysteries being unveiled. Coming to the section on explorers and exploration, Moser marvels at how our exploration efforts are now coming full circle, with our planet becoming "all wild again, all new" as a result of the changes we've brought upon it. Turning to the psychology section, she picks up Ludwig Binswanger's Being-in-the-World, a book she says is especially relevant to our future. "Why are we here?" she asks while perusing the title page. "What is it all about? What matters? Existential psychology. We're going to be asking that question with climate change for a long time."

Two additional highlights of Cappellin's time with Moser are their visit to a climate grief support group and an idyllic hike through the countryside in which they whimsically banter about dreams and the subconscious. In the group, emotions are raw but the feeling of family and unity couldn't be more uplifting. During the hike, Cappellin manages to find both a physical path through the woods and "the path of [his] own convictions."

Cappellin took part in a number of major environmental protests in between his interviews with experts, and he documents his involvement in them here in thrilling fashion. One especially exciting sequence shows him, along with at least a thousand other protesters, occupying an excavator at a German coal mine. They link hands and gaily charge toward a line of police waiting to arrest them. It's exhilarating, inspiring stuff, notwithstanding Cappellin's reality check at the end, in which he laments that all the group has managed to do is stop "one lone monster among the thousands currently tearing at the globe."

The film briefly features other experts beyond the main three highlighted thus far in this review. Their segments, together with Cappellin's thoughtful reflections in between, give viewers plenty of weighty issues to ponder, including human values in an age of limits, the merits of survivalism versus community, the role of civil disobedience in making change and the need for new stories with which to make sense of the world.

Early on in Once You Know, one expert asks whether we might be better off not knowing about the truth of our situation. He suggests that for the sake of our mental wellbeing, obliviousness might be the best course. This is a question that Cappellin and many others featured in this film have grappled with mightily. In the end, however, the film comes down on the side of knowing about and accepting the reality of humanity's mounting challenges. Cappellin sums it up with customary eloquence. Speaking for himself and those who have joined him on the journey to acceptance, he concludes, "After the milk and honey of carefree life, after the searing fire of knowledge, as we navigate between nightmares of apocalypse and fantasies of infinite progress, we now need to find a new path."

Now available on digital platforms

*******

If you enjoyed this review, you might find Joshua Smith's wonderful book Botanical Treasures a worthwhile read.