11/19/2022

The seed for this book was planted when author John Michael Greer learned that Grist Magazine had launched a climate fiction contest. Greer had long been critical of Grist, believing that it catered to affluent, "overprivileged" people who want to be told that someone else is responsible for the environmental damage caused by their consumption, and that someone else will fix it. He was similarly unimpressed by the contest guidelines, finding their call for stories that "put people and planet first" to be inherently self-contradictory ("[T]here's only one spot at the head of the line," he later rebutted), and their use of buzzwords like "intersectionality" to be mere social justice virtue signaling.

On a lark, Greer entered the contest with a story that followed the letter of its guidelines while gleefully violating their spirit. His story posited a future in which climate change has been greatly ameliorated through exactly the sort of individual sacrifice he believed Grist and its readership to eschew–albeit taken to a horrifying, if poetically just, extreme. Ever the provocateur, Greer hoped to get a rise out of Grist's editors and was somewhat disappointed when the inevitable rejection letter took the form of "a bland generic rejection slip instead of a scream of outrage."

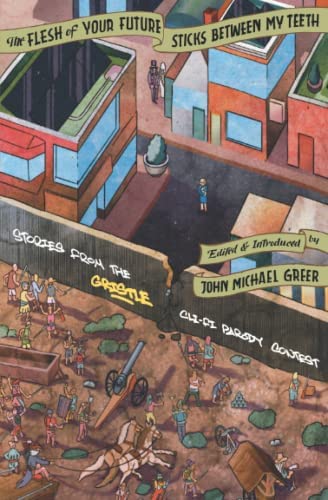

Within the community of commenters on Greer's blog Ecosophia, a good time was had by all in mocking the contest and the unintentional satire of some of what proved to be its top entries. Eventually Greer decided to launch a contest of his own in reaction against Grist's. He called it the "Gristle Cli-fi Parody Contest," and its winning entries make up the exuberant exercise in satirical iconoclasm that is The Flesh of Your Future Sticks Between My Teeth.

The stories in this collection cover a wide swath of styles, tones and genres. Some are comedies–their humor ranging from farce to tragicomedy to dark humor–while others are dramas, and still others tragedies. Their one common link is their determination to skewer sacred cows. Their satire isn't directed solely at environmental hypocrisy; it also pokes fun at some of the excesses of today's social justice movement, seemingly in response to the Grist contest's emphasis on such non-climate-related things as intersectionality and learning to use new pronouns as keys to solving the climate crisis.

Some stories achieve their satire through comic exaggeration. Haldane B. Doyle's "The Recalcitrant Savior" is about a future U.S. president whose advanced age and propensity for gaffes have been taken to truly absurd extremes. The main characters in Simon Sheridan's "Tell it to the King of Sweden, Honey" are burlesques of environmental activist Greta Thunberg and the stereotype of the "Karen" (named Gretel Hamburg and Karrenn Smith Hernández Wong, respectively). And the would-be climate savior in Mark White's "Power to the People" finds his biggest obstacle to be the tyranny of the comically oversensitive PC brigade within his own workplace.

Morbid hilarity is the prevailing tone of Roger Arevalo's brilliant "Human-Derived Product," whose viewpoint character runs a business that recycles human cadavers. In this future, resources are so scarce that there's huge money to be made in turning human remains into nearly every conceivable consumer product, from food to clothing to fertilizer to fuel to glue. The narrator tells us of craftspeople who turn human bones into buttons and broaches, vegans who eat human meat because it's animal cruelty-free, music fans who pay to have their hides made into drum skins after they die and a racecar driver who arranges to be distilled into fuel. In defense of his business, the narrator points out that death has always been profitable, that those who surrender their bodies to him do so willingly and that his employees all make respectable wages.

Linda Peer's "How the Conspiracy Theory Generator Saved the World" uses a beast fable to critique the widespread human misconception that our species somehow exists outside of nature and can thus hold dominion over it. In this tale, it turns out that a secret society of dogs–some of them AI-enhanced–has really been pulling the strings all along. Through a series of elaborate ruses, the dogs have been slowly but surely guiding humans toward sustainability.

Not all of these satires are good-humored. There are no laughs to be had, for example, in Daniel Crawford's harrowing "The Penitent Lands," in which today's quest for social justice has been taken to genocidal new heights. Ron Mucklestone's "The Merchant of Progress" is equally bleak with its tale of a man who awakens from 60 years of suspended animation to a nightmare world dependent on slave labor (now that the fossil fuels powering today's industrial society are gone) and faces grave punishment for his refusal to accept this new world. And Greer's own afore-alluded-to "A Modest Contribution" is no less brutal in its depiction of a better world arising from unimaginable loss.

"Kathy vs. the Barbarian Horde" by E. E. Hills pointedly illustrates the folly of choosing to police people's speech rather than ward against real crime. The story takes place in an ultra-woke future version of Berkeley, California that has come to rely on "diversity staff," rather than armed police, to keep the peace. America is in steep decline by this point, but Berkeley has thus far managed to beat back the barbarian hordes thanks to a super weapon called the Peace Protector. But when a widespread satellite outage renders this lone defense system utterly useless, the people of Berkeley come to regret their habit of persecuting wrong-thinkers rather than those who are doing actual harm through their actions.

The classic satirical device of the travel narrative is used effectively in Lester J. Bear's "Atlanta is Broken" and Ian Duncombe's "Scions of the High Road." Bear's travelers embark on what we today would call a business trip, but which seems more like a suicide mission in the future of this story, in which industrial-era technology is in decline due to dwindling fuel supplies, America is functionally Balkanized and violence runs rampant. The travelers in Duncombe's tale represent wokeness taken to its logical extreme, with their complaints of "cis outcast groups" and sun worshippers "[m]asquerading in the Mestizo race's skin color" by letting themselves tan so deeply.

Justin Patrick Moore's "A Chi Town Doctor" is partly an adrenaline-pumping tale of gang warfare in a lawless, deindustrial Chicago, and partly a rebuke against some of the core assumptions of our modern world. In its gritty depiction of urban decay and its chaotic bricolage of old and new technologies, it challenges the notions that progress is inevitable and that technologies from the past have nothing to offer us. The population of this Chicago is wildly diverse, yet civil rights don't exist as we now know them. People travel by horse, rickshaw, skateboard and biodiesel train; they fight with everything from slingshots to long-range acoustic devices. Occultism has made a big comeback in medicine.

It's hard not to be inspired by the spirit of this book. At a time when so many people are in the habit of self-censoring for fear of the opprobrium that is heaped on those who so much as nick one of today's cultural tripwires, here's a book that dares to barrel right through the tripwires in order to say things it thinks need to be said.