Oregon's Willamette Valley is a hundred mile long, two-million acre stretch of prime cropland bordered by a dense, eco-rich coniferous forest. The climate is mild; wet in the winter, dry in the summer. It is excellent for raising livestock and farming, with soil particularly suited for many types of grasses and legumes. There is tremendous flexibility in what can be grown and the way that the various field crops can be rotated for the health of the land. Home to a variety of fish and other wildlife, the Willamette River basin is essentially a garden valley, Oregon's own little piece of Eden. The Lane County Fairgrounds site is in the city of Eugene at the south end of this valley.

The impetus behind the Fairgrounds Repair Project is more than just a make-over for an out-of-date county fairgrounds site. The larger premise is to promote community action addressing concerns for climate change, peaking oil production, and the related issues of food security and sustainable agriculture. One primary intention of the project is to facilitate the relocalization of the regional food system and revitalize Willamette Valley agriculture.

The word "relocalization" suggests that what was once local is no longer local and that it should be. Nothing could be more apt than applying this concept to agriculture and food production in the Willamette Valley. While the globalization of the market place has expanded trade with a rich and diverse new array of products and product sources, the long-term effect of the global marketplace has been to take the local out of what we buy, particularly what we eat–wherever you live. In the Willamette Valley, for instance, less than five percent of what the populace eats comes from within the region, meaning ninety-five percent of the valley's food is imported. These numbers apply across the board to just about any area in the United States, but with particular poignancy for the Willamette Valley because it is a region that contains quite a bit of fertile farmland and once provided its residents will more than half of what they ate. (See Relocalizing Eden.)

Certainly international trade offers many positives. More things are available to a wider selection of people and often at cheaper prices. It also creates a sense of economic interconnectedness for all peoples of the world and, in the case of food, allows regions to enjoy products that canít be grown locally. In spite of this, however, the expansion of global markets has been at the cost of regional economic balance, especially in the food sector. Agricultural areas throughout the world now tend to focus on the one or two local crops that bring the most profit in the global market instead of growing a diversity of crops for consumers in their own region. This dynamic not only detracts from the agriculture balance and sustainability of the region, but it is also causing communities to lose the ability to feed themselves from local sources because they rely so heavily on distance markets for their food. Local food production diminishes because it seems unnecessary, and the local food system infrastructure supporting that food production goes out of use and often disappears. This has happened in Oregon's Willamette Valley. There is little or no long-term food storage. There are only a few local food processors. And less than twenty percent of the available farmland is used to produce food. What was once a vibrant working regional food system has been reduced to a skeleton.

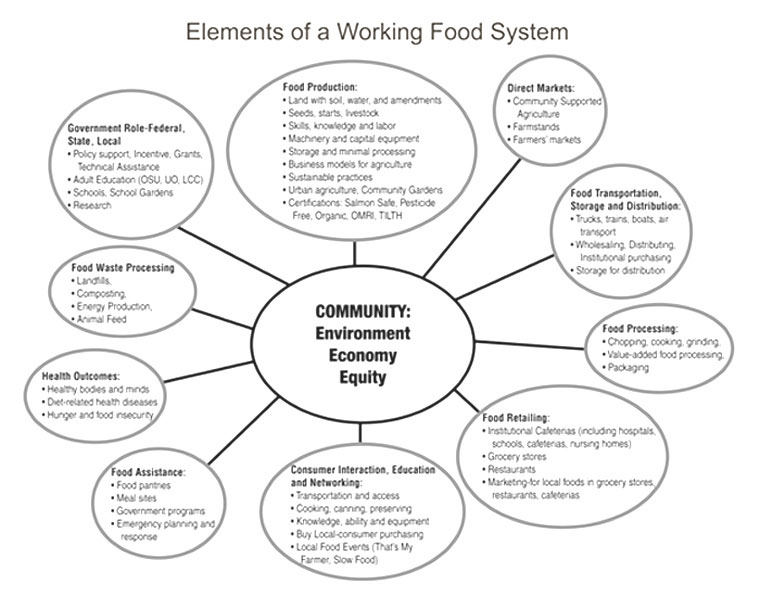

When viewed through the lens of food security and rising fuel prices, it is clear that this dynamic is leading us in the wrong direction. (See Lane County Food Security Assessment.) One accepted strategy to increase local/regional food security is to have a working food system. This means re-establishing the local capacity to grow food products, process them, store them, distribute them, and market them. This would be a wise direction for the Willamette Valley.

Thus part of the Lane County Commons' conceptual purpose is to facilitate the relocalization of the regional food system by rebuilding lost infrastructure, including a year-round farmersí market to stimulate the sale and production of local food products, a produce aggregation and minimum processing depot for the cleaning, sizing, and boxing of local products, a food storage and distribution warehouse to assist in the efficient dispersal of those food products, a regional agricultural center to facilitate the sharing of information and resources between local farmers, and two grain silos to increase food storage capacity in the area. (See Agricultural Resource Center and Food Hub.) This is in addition to the Lane County Commons' onsite organic and sustainable gardening demonstrations, its onsite composting workshops and demonstrations, and its onsite relationship with the Oregon State Extension Service that teaches classes in master gardening, composting, food preparation, food preservation, and nutrition.

When complete, the Lane County Commons will be a working food hub that incorporates wholesale and retail food sales, distribution, and storage at a single location and adds one critical building block to process of the relocalizing of the Willamette Valley food system–something that many believe should be happening all over the United States. (See The Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project for the story of another effort to promote this regional strategy.)