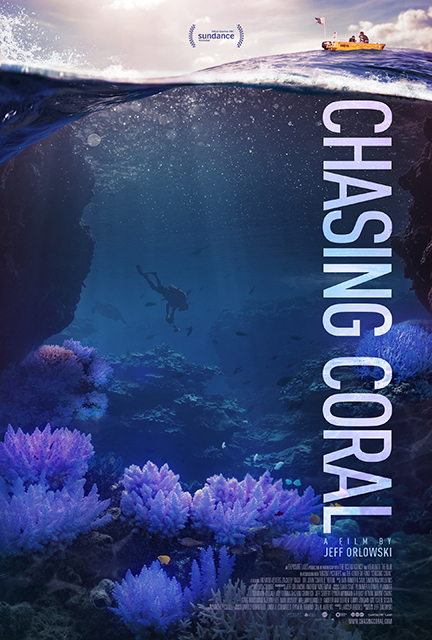

By raising sea temperatures, climate change is eradicating the world's coral. Because coral reefs provide sustenance and protection to vast numbers of humans and marine organisms, it would be a big deal for them to go extinct. The El Niño that lasted from 2014 to 2017 caused a global-scale mass coral bleaching event of unprecedented severity, which damaged a majority of coral reefs around the world. The makers of Chasing Coral managed to document this calamity. Their film is a love letter to an astonishing group of disappearing animals, an elegy to the scores of these animals that have vanished thus far and a wake-up call to humanity.

The documentary follows the work of a team led by ocean conservationist Richard Vevers. A former London ad executive, Vevers left advertising more than a decade ago to professionally pursue his passion for underwater photography. In 2010, he founded The Ocean Agency, a Newport, Rhode Island-based nonprofit devoted to protecting marine life. Two years later, he became executive director of the XL Catlin Seaview Survey, a major scientific expedition that used pioneering underwater imaging technology to visually record the composition and health of coral reefs. There have been numerous follow-up expeditions since that first one, and together they've produced a vast body of images that is now being studied by scientists worldwide. The images are also accessible to the public through an online database called the XL Catlin Global Reef Record.

The first year of the XL Catlin Seaview Survey also happened to be the year when the award-winning documentary Chasing Ice was released. Directed by the filmmaker who would go on to direct Chasing Coral, Jeff Orlowski, the earlier film chronicled nature photographer James Balog's efforts to photographically capture the disappearance of Arctic ice. Vevers tells us that when he first saw Chasing Ice, he was struck by how similar Balog's project was to his own. Both sought to convey the reality of climate change not through statistics or abstractions, but through vivid visual evidence. Vevers immediately contacted the film's director to let him know about his work documenting climate change's impact on the undersea environment. Orlowski was captivated and the two soon began collaborating on the project that became Chasing Coral.

Their finished film opens with a breathtaking montage showing divers photographing reef-dwelling sea turtles. Vevers, our narrator, speaks with wonder about "the magic of the ocean" and how time seems to slow down under its surface; and the photography and musical score successfully evoke this sense of timeless, otherworldly enchantment. The documentary proceeds to take us around the globe and introduce us to coral of all shapes and sizes. We go from the Florida Keys to American Samoa to Australia's Great Barrier Reef; and we glimpse majestic gardens of antler-like elkhorn coral, brilliantly colored sea fan coral and still other coral that look for all the world like unassuming gray boulders. By way of some truly hypnotic time-lapse photography, we observe coral feeding by repeatedly extending their snowflake-like polyp tentacles over successive days and nights.

Chasing Coral also zooms out to show us some of the fascinating creatures that call coral reefs their home. Marine biologist Ruth Gates aptly refers to the Great Barrier Reef as "the Manhattan of the ocean" because it is as densely packed, diverse and active as a New York intersection. We're treated to a symphony of naturally occurring sounds that includes grunts, purrs and even a birdlike dawn chorus. We observe interspecies hunting partnerships, fish providing protection to coral reefs and still other fish eating coral to later excrete it as sand. (It's revealed that fish of this latter family–the parrotfish or Scaridae family–produce a good share of the sand that winds up on Earth's beaches.)

As with Chasing Ice, this film focus as much on the human drama that unfolded during filming as it does on the phenomenon the researchers were there to record. The scientists, technicians, scuba divers and other experts who embarked on the surveys faced tough technical challenges and were met with some discouraging setbacks. Because no one had ever done what they were attempting, they had to develop a completely new type of encased camera that could operate underwater remotely for months at a stretch; and with the El Niño upon them, they had a tight deadline. Their first cameras failed, producing months' worth of fuzzy, useless footage. But the team rallied and retooled the cameras, and the second-generation cameras yielded a literal database of images.

We share in the sorrow of the film's main characters as they watch the destruction of once-rich coral ecosystems. Diver Zackery Rago's anguish is especially palpable. Rago has a special connection to coral, so his work amid the disintegrating coral of the Great Barrier Reef becomes almost unbearable for him. During the team's final days there, he confides with a faraway gaze and a tremor in his voice, "I'm not even mad that I'm leaving, because it's just so miserable here."

Another powerful scene comes toward the film's end, when the team presents some of its time-lapse images at an international symposium. As one coral colony after another deteriorates into a vacant, algae-coated boneyard, the documentary cuts between the pictures on the screen and the increasingly pained faces of the scientists watching. It's a human and deeply affecting scene.

Though Chasing Coral follows the same basic template and many of the same beats as Chasing Ice, I don't fault the film for its repetition. The original template works brilliantly, and the new story has much the same dramatic arc as the first one. Indeed, we sense in the two films' central characters something of a literary motif: the devoted explorer and nature lover who feels compelled to visually communicate the threat of climate change to the rest of society; assembles a team to do so; successfully manages the rigors of working in a remote, extreme environment; and brings back a frightening, eye-opening portrait of human-caused mass devastation.

A significant difference between Chasing Ice and Chasing Coral is that while the earlier film spends a good deal of time debunking those who dispute climate science, the new film chooses not to engage with such individuals. To me, this is an improvement. Attempting to sway staunch climate change deniers through reasoned arguments is generally a lost cause. How much more effective it is to let the visuals tell the story. Indeed, the man at the core of Chasing Ice admits he refused to accept the reality of climate change until he saw firsthand the toll it was taking on his beloved glaciers through time-lapse photographs.

Chasing Coral's biggest shortcoming is its ending, which is a case study of cognitive dissonance if I've ever seen one. After explaining at length why coral ecosystems are a likely casualty of climate change, the film concludes with talking heads asserting, without evidence, that it isn't too late to save the coral, followed by a list of countries committed to transitioning away from fossil fuels. It comes off like a cancer doctor attempting to reassure her terminal patients by telling them that human ingenuity is fully capable of curing cancer and that lots of researchers are working on a cure. Chasing Ice thankfully had no such ending. It concluded by summarizing the continuing efforts of James Balog and his team, which worked because we had become emotionally involved in Balog's story–whereas we had zero investment in seeing some forced, unearned hopeful ending. Orlowski would have done better to end Chasing Coral similarly.