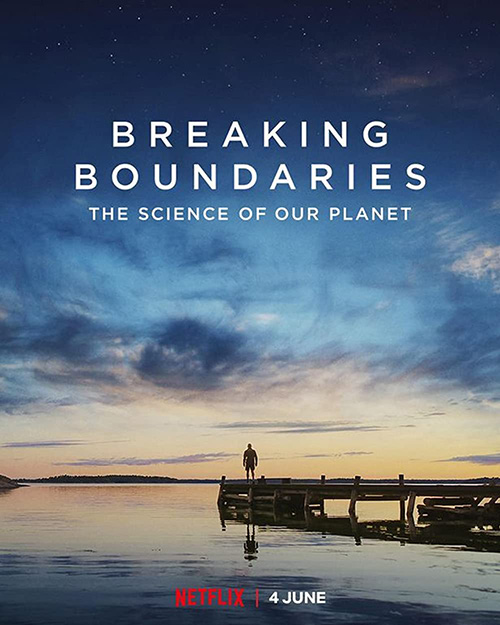

The Science of Our Planet

Breaking Boundaries is a well-intentioned but bungled documentary about the ecological destruction currently being wrought by industrial humanity. While the film hits on all the core issues we're facing, and correctly highlights the importance of individual action in response to them, its lean runtime keeps it from going into depth about any of the many complex topics it covers. The material cries out for a docuseries, not a lone, less-than-feature-length documentary. Thus, the film represents a missed chance, and one that is all the more disappointing for its squandering of the inestimable talents of the great natural historian and Emmy-winning narrator David Attenborough.

The film does earn points for a nice double-entendre title. On one level, the word boundaries refers to points beyond which humanity's impacts on a given natural system begin triggering large, nonlinear changes that threaten the stability on which human civilization depends. On another, it no doubt signifies the boundaries of our collective imagination that have thus far kept us from rethinking our mad craze for infinite growth on a finite world. The former are planetary boundaries and consist of the following: the climate, biosphere integrity, critical biomes, the water cycle, the nutrient cycle, ocean acidification, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol pollution and the release of novel and/or toxic chemicals into the environment. The latter are not explicitly defined but presumably consist of the deeply ingrained patterns of thought that have enabled those of us in the developed world to rationalize our profligate lifestyles.

Other pluses include splendid nature footage—spanning a stunning array of habitats across several continents—and numerous concrete examples of the interconnectedness among all these seemingly disparate settings. It is while in this mode that the film most feels like a David Attenborough documentary, for Attenborough's genius lies in his ability to enthrall us with wondrous scenes of natural beauty while simultaneously educating us about the science at work within them.

Even if you've never thought of things in terms of the nine-boundaries framework, you're still likely to already be aware of most of the information presented here regarding humanity's predicament, provided you've been paying any kind of attention to the important goings-on of planet Earth. Still, the film does sometimes manage to transcend the mere recitation of well-known facts and figures, and get us emotionally involved in the scenes of devastation to which these facts and figures speak. In one scene, we see the anguish of an Australian cockatoo researcher as she visits the charred remains of a once-thriving bird habitat following its destruction in the 2020 wildfires. In another, a coral reef researcher has to take a moment to compose himself in the midst of describing how climate change is killing the Great Barrier Reef. Both these scenes are human and poignant.

The topic that receives shortest shrift is that of solutions to our crisis. Only the briefest mentions are given to the potential roles of renewable energy, tree planting, healthy-eating initiatives and the elimination of waste from manufacturing processes in ensuring a livable future. Though I credit the film for stressing above all the need for individual change–without which there can be no broader societal shift toward sustainability– I would like it if this theme had been explored on something more than the most superficial of levels.

The documentary unfortunately bears marked traces of what author James Howard Kunstler calls techno-narcissism, or an excessive faith in our own species' technological abilities. A key symptom of techno-narcissism is what Kunstler calls the Fallacy of Exquisite Measurement. To quote from page 196 of Kunstler's 2020 book Living in the Long Emergency, this states: "[T]he ability to measure things down to very fine detail does not automatically confer a power to control things." We see this fallacy at play in the reverence paid to the work of one of the film's key experts, Swedish Earth scientist Johan Rockström of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research–in particular, Rockström's chart of global temperature variability over the past 100,000 years. One can't help feeling that this graph is being brandished like a talisman of humanity's ability to vanquish any problem it can plot on an x-y graph.

The same applies, of course, to the whole construct of the nine planetary boundaries. The film posits that now that we've managed to identify these boundaries and pinpoint where we are with respect to each of them, all that's left is for us to target them with the full weight of our almighty technological prowess. In support of this claim, we're reminded of how humanity succeeded in arresting the destruction of the ozone layer by taking aggressive action to ban CFCs worldwide. This success story is a tired and rather tenuous one. Our capacity to eliminate one particular class of chemicals from our lives hardly translates into an ability to wean ourselves from the master resource that enables every aspect of modernity.

This leads me to the film's severely circumscribed notion of limits. In keeping with the conventional folly of our time, it acknowledges the Earth's limits to our environmental impacts, but ignores the reality of limits to the resources we like to think we can use to dig our society out of the crisis we've made for it. For example, we're shown an image of solar panels on a hillside, and the subject of renewable energy is briefly touched on a few times, but that's as far as the film goes in its discussion of alternatives to fossil energy. The unspoken assumption seems to be that the ability of industrial-era technology to boost renewables' share of the world energy mix from a mere fraction to the whole enchilada is a foregone conclusion, notwithstanding the crushing issues of energy density and scalability that stand in the way of such a feat.

For me, the low point of Breaking Boundaries, and the height of its techno-narcissism, is Attenborough's coda at the end. Affecting a tone of sage-like wisdom–no matter the fatuousness of what he's about to say–he avows, "[W]e now have the capacity to act as Earth's conscience, its brain, thinking and acting with one unified purpose: to ensure that our planet forever remains healthy and resilient; the perfect home." Earth's survival as a life support system hardly requires our intelligence. The biosphere has endured extinctions of almost inconceivable magnitude just fine without us. Nor are we in any position to secure its livability for the remainder of Earth's habitability window, since our species will have long since gone the way of all species by the time Earth has reached the end of her term as a haven for life.

But again, my main fault with this film is its decision to compress a whole series' worth of material into one sub-feature-length outing. At the very least, the runtime should have been bumped to two hours, with the first hour spent on the particulars of our planetary situation and the second on potential responses–much as in the immeasurably superior 2007 film What A Way To Go: Life at the End of Empire. As it is, this one brief entry is more like a compilation of news headlines and ad slogans than it is a serious exploration of any of the various topics it purports to address in the course of its overstuffed 73 minutes.

*******

If you enjoyed this review, you might find Joshua Smith's wonderful book Botanical Treasures a worthwhile read.