Stories from Our Imperiled Biosphere

For me, the greatest joy in reading Ross West's eco-short story collection The Fragile Blue Dot lies in the sheer brilliance of imagination and storytelling prowess on display in each piece. West's storytelling range is truly impressive; his prose, evocative and poignant; and his characters, unconventional and challenging. He uses a host of clever techniques to deliver exposition and drive his narratives forward. The situations he imagines are inventive and revealing.

The opening story, "Chrysalis," is a pointed critique of industrial society's faith in technofixes as solutions to environmental crises. Our main character, Lisa Contreras, is a geologist for green tech giant Sun Vista; she's currently stationed at a solar site in the American desert, part of a sweeping U.N. climate initiative. At a bar, she meets Professor Maddox, a disillusioned lepidopterist who once helped halt construction on a massive wind farm that would have endangered the habitat of the pygmy blue dot butterfly. But a new law known as the Clean Earth Act has overridden those protections, at the cost of the butterflies' last habitat. Lisa joins Maddox on a journey into the desert, where they find a lone blue dot chrysalis–perhaps the last. We're left to reflect on the irony of a supposed climate solution that has played a part in destroying the very biodiversity it was meant to save.

The story described above is one of several whose main characters undergo personal transformations as they confront both the scale of our ecological crisis and their complicity in it. In "Plans," a travel writer begins to question the environmental cost of his work and attempts to steer his company toward a more sustainable path, even at great personal cost. In "Tool," a simple act of artistic expression at a climate conference leads to a global movement, reshaping both the narrator's view of activism and the emotional landscape of climate grief. And in "The Real Manhattan," a journalist assigned to cover a climate icon loses respect for her as she comes to see the contradictions in her lifestyle and ultimately chooses to write a more honest, though professionally risky, story about her.

"Untellable Tales, Chapter XXXVII" is a pseudo memoir with a touch of espionage. Presented as a chapter from the memoir of a nameless former intelligence officer from an agency known only as "the Company," it tells of an unsung hero within the same agency. This figure, Aldous Pritzker, put forward a revolutionary proposal to reallocate military funds into a global environmental initiative, but faced bureaucratic resistance at every turn. Though his plan was eventually adopted, Pritzker went uncredited. Then again, we sense he wouldn't have wanted the spotlight anyway.

For connoisseurs of satire, "Cowabunga Sunset" is not to be missed. It takes place in a future plagued by drought, famine and water wars and centers on an amusement park that offers an idealized beach experience now nonexistent in the real world. The park is doing great business until a government agency called the Office of Cultural and Historical Disambiguation orders it to be shut down for violating laws against historical misrepresentation. Before the park can be reopened, it must be remade into a dystopian "Beach Museum" accurately reflecting the environmental devastation of the outside world. Among the new attractions are polluted waters and shorelines and an educational display called the "Climate Migrant Beach Corpse" exhibit.

Ross' stories have a penchant for troubled people and tragic turns. "The Man Who Almost Saved the World" is about an aging scientist who–armed with gasoline and a match–makes a final, desperate attempt to draw attention to the need for population control as a solution to climate change. "Ophelia's Understudy" is told from the perspective of a bookstore browser who accepts a strange offer from a manic author, only to see her mentally unravel during a trip they take together across Europe. In "The Burning Planet," a filmmaker's documentary about a radical environmentalist ignites nationwide unrest, leaving him haunted by the unintended consequences of his creation. "Downsizing" is about a laid-off power plant supervisor who, while drunkenly selling off his family's belongings in preparation for their cross-country move, makes a tragic misstep. And in "If Anything Changes," a feuding couple exploring ice caves near Reykjavík, Iceland reaches a tentative reconciliation–only for tragedy to strike. The scenarios are riveting and telling.

In much the same vein, "Boiling Alive" follows a young activist's journey from a hesitant observer of eco-terrorism to a fervent believer preparing to carry out his own attacks. His radicalization stems from a deep personal trauma: the loss of his childhood home to a devastating wildfire. Since then, he has come to view climate collapse not merely as a crisis, but as a war–one that demands immediate and uncompromising resistance. In the opening scene, he sits alone in a diner at 3 a.m., quietly sketching and waiting to film the explosion of a big box store warehouse–an act of eco-sabotage meant to protest the environmental damage caused by the store's reliance on cheap overseas merchandise. By the end, he has resolved to take a more active role in the future operations of the radical activist group to which he belongs.

In some stories, the ecological themes are subtextual rather than overt. The only direct connection to ecology in "The 50 Faces of Albert Einstein"–in which a retired diplomat turned teacher makes a journey to visit an ailing man linked to a cherished keepsake–lies in the fact that the protagonist teaches climate diplomacy. Similarly, in "Smoke, Fire, Ashes," a young woman's passion for environmental activism is the sole ecological thread in a brilliantly told meditation on the fragility of human relationships rendered by way of a strained family vacation. I like how these stories are first and foremost character-driven narratives, with environmental themes subtly woven into the background. Not that the others are heavy-handed–it's just that this quieter approach offers a nice change of pace.

While I don't have a single favorite story from the collection, one that especially stood out to me was "All By Herself," a tightly written piece told entirely through a phone call between estranged parents. When Suze calls Gerald to ask if he's seen their daughter Kaylee's social media post announcing her hunger strike at City Hall for climate justice, it's clear he hasn't. As Suze explains the risks–Kaylee's plan to fast for a full week, the coming media coverage, exposure to the elements–Gerald's lack of awareness about his daughter's life becomes increasingly apparent. The dialogue conveys a lot of information without ever feeling expository. As the plot progresses, the prose becomes increasingly stripped down–dialogue tags disappear, scenes compress–and this newfound leanness heightens the emotional urgency and increases the narrative momentum.

Throughout the collection, the caliber of West's writing never ceases to impress. My favorite Westian hallmarks are his rich, onomatopoeic descriptions, dry, deadpan humor, sudden emotional reversals and inventive approaches to delivering backstory. One particularly cunning instance of the latter comes when the protagonist of "Ophelia's Understudy" mentally recounts, in the form of game show-style questions and answers, all that she's come to learn about her new companion in the course of a single car ride together.

West is a seasoned essayist, journalist, poet, and fiction writer whose work has appeared in prestigious publications like Orion, Best Essays Northwest and Best of Dark Horse Presents. He has served as editor for Oregon Quarterly and Inquiry–a research publication at the University of Oregon–and as the university's science writer. The Fragile Blue Dot is his debut fiction collection. Few fiction anthologies have left me so eager for a follow-up.

*******

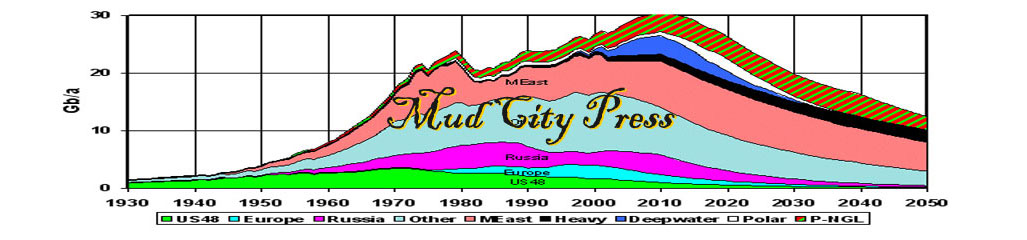

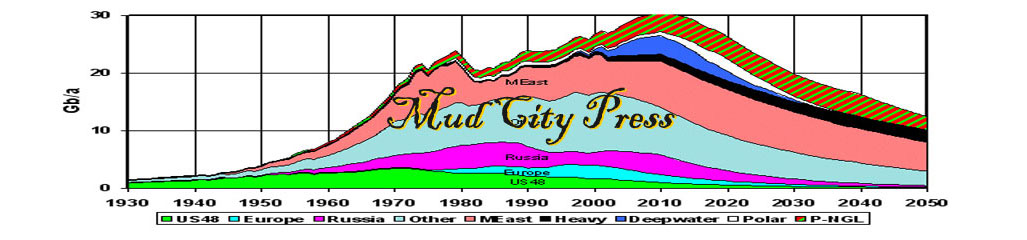

If you enjoyed this review, try Prairie Fire. Imagine Tom Clancy writing a multilayered thriller about peak oil.