Home | Spaceship Earth | Book Reviews | Buy a Book | Bean and Grain Index | Short Stories | Contact | Mud Blog

By Dan Armstrong

Introduction: The Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project is a step-by-step, ground-level endeavor aimed at the transformation of agriculture in Lane, Linn, Benton, and Lincoln counties at the south end of Oregon’s Willamette Valley, an area containing roughly 750,000 acres of farmland, approximately 450,000 acres of which is used for cropland. This region which once produced a wide variety of food crops is now dominated by farms growing fescue and rye grass for the global grass seed market. A historically hearty regional food system is now focused on ornamentals and utilizes less than twenty percent of its cropland acreage for food. In these changing times of rising food and fuel prices, it is imperative to bring more balance and diversity to Willamette Valley agriculture. The Bean and Grain Project seeks to do just that by converting good-sized parcels of grass seed acreage into plots for organic beans, grains, and edible seeds as a critical first step to reinvigorating the regional food system.

Harry MacCormack, co-founder of Oregon Tilth and owner of Sunbow Farm in Corvallis, Oregon, provides the vision and inspiration for the Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project. MacCormack has farmed in the south Willamette Valley for forty years, developing organic farming techniques, helping establish the first federal standards for organic certification, and experimenting in the field with a wide variety of grains, legumes, and edible seed crops.

Context: The world currently faces unprecedented challenges due to long-term resource mismanagement and environmental degradation. While demand pressures have steadily increased for petroleum, wood products, world fishery harvest, industrial metals, and clean water, recent stresses in the grain market have put a focus on food production and agriculture that very few could have imagined five years ago. Almost overnight it seems food security has progressed from a Third World concern to the forefront of First World issues.

Background: Over the last sixty years, world food systems have gone through a period of steady change. In the years following World War II, food production and distribution in the United States was largely regionally-based with complete or nearly complete local food systems. Most regions were consuming in excess of fifty and upwards to ninety percent locally grown food. With the building of the interstate highways during the 1950s and the new suburban model of America, there was a gradual movement away from independent regional food systems to larger and more centralized industrial units. A growing world population and increasing U.S. grain export through the 1960s and 1970s led to further food system consolidation at a world level and an accelerating trend in the United States away from family farms to large industrial farms. Facilitated by high-speed computers and vast new electronic communication networks, the 1980s and 1990s brought the advent of our current global food system, organized and maintained by giant transnational processing, distribution, storage, and shipping conglomerates.

Though the globalization of the market place has expanded trade with a rich and diverse array of new products and product sources, it has been at the cost of regional economic integrity, especially at the local level and especially for local food systems. Regional agriculture has turned to monoculture and the targeting of specific global markets, diminishing diversity in what is grown for local markets and lending to the deterioration of regional food system infrastructure. Communities have actually lost the ability to feed themselves from local sources by relying too heavily on distance markets for their food.

At a national level today, it is estimated that Americans are eating less than two percent locally grown food, and most of what is consumed comes from more than fifteen hundred miles away. Globalization has essentially turned U.S. agriculture and our food systems inside out. At the very center of this is the use and abuse of fossil fuels and hydrocarbon by-products.

It is often overlooked, but nearly every aspect of our current food system is based on petroleum and other carbon-based inputs. Soil nitrogen levels are maintained by fertilizers made from hydrocarbon gases. Pests are fought with petroleum-based pesticides. Weeds are eliminated by petroleum-based herbicides. Fields are cultivated and harvested by machinery powered by petroleum-based fuels. Food products are transported by trucks or trains or airplanes powered by petroleum-based fuels. Foods are processed with machines run by electricity generated by fossil fuels. Foods are packages in plastics made from petrochemical products. We cook with fossil fuel derivatives. From field to distributor to store to kitchen cabinet to stove, our entire food system flows upon a stream of petroleum. This system has evolved and grown through a period when petroleum and natural gas were irrationally cheap. That era appears to be over. The cost of a barrel of petroleum has increased ten fold in the last ten years. Oil production has or will soon peak. Hydrocarbon-based agriculture and its global food system is a literal and figurative dinosaur. Freight costs alone ensure that our food systems must change.

Add the detrimental environmental impacts of industrial farming techniques–aquifer depletion, topsoil loss, petrochemical contamination of the watershed and other biota, toxic residues on or in crops themselves, and it is becoming increasingly clear that changing the way we farm is both sensible and necessary. Creating sustainable regional food systems based as much as possible on organic inputs and as independent as possible of petroleum fuels, should be one of humanity's highest priorities. That is the exact purpose of the Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project, rebuilding a regional food system in the Willamette Valley.

Related Factors: Peak oil is a reality. Oil production is reaching a maximum. This means the cost of all petroleum products are on the rise and will continue to rise for the foreseeable future. This trend has already made a significant impact on the agriculture industry with climbing prices for chemical fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, farm machinery fuel, and product transportation. The net result is that foods of all kinds are getting more expensive. The entire food system must be remodeled to diminish petroleum inputs as much as possible.

Labor cost differentials will be minimized by increasing petroleum prices. Cheap freight costs during the last forty years have facilitated a comparative labor advantage for Second and Third World countries. Produce grown in countries as far away as South America has been cheaper than locally grown produce because of low farm labor wages and cheap fuel costs. The rising cost of fossil fuels will increase freight and refrigeration costs for food transportation and is likely to minimize the labor advantage of distant markets. Locally grown produce will gradually become more competitively priced against global imports with the clear advantage of also being fresher. Market stimulus will favor regional versus global food systems.

Climate changes are wild card in all future planning. Climate change will alter the world's agricultural landscape. Concerns for catastrophic weather events, changing rainfall patterns, diminished snowpack, and water supplies in general will become increasingly important agricultural factors. Food security will become an off and on problem for the First World. Famine potentials in the Second and Third Worlds will rise asymptotically.

World grain market fluctuations will be a constant source of concern. Fifty years of steady and predictable grain market surpluses have come to an end. A long drought in Australia, the push to grow corn for ethanol, a growing middle class in Asia, and other lesser factors have turned the grain market upside down in the last year. The price of wheat jumped from a rather predictable $3.50 a bushel to a very volatile $12 to $20 a bushel over the past winter. This kind of grain market fluctuation will cause more speculation at the global level and put greater pressure on world grain reserves and the populations of less developed nations.

Rebuilding regional food system infrastructure will be a priority. As stated earlier, one critical long-term effect of globalization on regional food systems has been the deterioration of local food system infrastructure. Regional food processors, distribution hubs, storage facilities, and markets are sorely lacking throughout the United States. Any increase of regional food production for local consumption must be matched by proportional infrastructure increases. At bottom, it must be emphasized that relocalized agriculture is aimed at rebuilding complete regional food systems not just growing more food to meet global demands. Essential to this idea is growing food first for local markets and then for global markets, if surpluses are available.

Bioregional Setting: The bio-region defined by the Willamette River watershed has the capacity to be one of the most bountiful in the United States. The Willamette Valley is a hundred mile long, two-million acre stretch of prime farmland bordered by a dense, eco-rich coniferous forest. The climate is mild; wet in the winter, dry in the summer. It is excellent for raising livestock and farming, with soil particularly suited for a wide variety of grasses and legumes. There is tremendous flexibility in what can be grown and the way that the various field crops can be rotated for the health of the land. With the potential to grow more than two hundred different food crops and being home to a variety of fish and other wildlife, the Willamette River basin is essentially a garden valley.

Historical Agricultural Picture: In the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, Willamette Valley agriculture produced a wide array of grains, fruits, and vegetables. At times wheat represented almost a third of what was harvested. Barley, oats, snap peas, and sweet corn were also significant crops. Tomatoes, broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, potatoes, onions, cucumbers, peaches, raspberries, strawberries, hazelnuts, and squash fill out the mix. Prior to 1970, Willamette Valley farmers were providing more than half of what the valley residents were eating. Though there were items which did not grow in the valley and the population was about half of what it is today, the region did have the agricultural capacity and food system infrastructure to feed itself.

Current Agricultural Picture: In the early 1980s, as wheat prices eased off what were then record highs, Willamette Valley farmers began a steady conversion of wheat acreage to grass acreage for the production of grass seed. This grass seed is shipped all over the world for forage, suburban lawns, and golf courses. Grass seed is now the valley’s most important cash crop. Sixty percent of all the acreage that was harvested in the Willamette Valley in 2006 was for grass seed. That was over 500,000 acres. At the same time, less than 30,000 acres of wheat were harvested in the valley, down from a record high of 270,000 acres in 1982.

In other words, high-value Oregon cropland is being used primarily to grow a non-edible luxury item instead of food. Globalization has enabled specialized and long distant markets while at the same time diminishing food crop diversity at home. The net effect is that the Willamette Valley populace is now eating less than five percent locally grown food.

As alluded to earlier, an additional concern is the use of petrochemicals to enhance the productivity of all variety of foods and grass seed crops. It has been thoroughly documented that the long-term use of hydrocarbon-based fertilizers wears out the soil. After a while, the soil is essentially dead, devoid of bacteria and microorganisms. The soil becomes little more than a medium for washing through chemical fertilizers. Even in a region as fertile as the Willamette Valley, this kind of agriculture can not endure and is essentially a dead end.

Along with hydrocarbon-based fertilizers, other chemicals are used as pesticides and herbicides to protect crops from pests and weeds. Farming with these kinds of chemical inputs can be tentatively successful, but what is produced is tainted by chemical residues. Excess chemicals are washed away by rain or irrigation and enter the groundwater systems and eventually the entire watershed. High levels of agricultural toxins have been found in Willamette Valley ground water and must be consider a health issue–again pointing to a dead end.

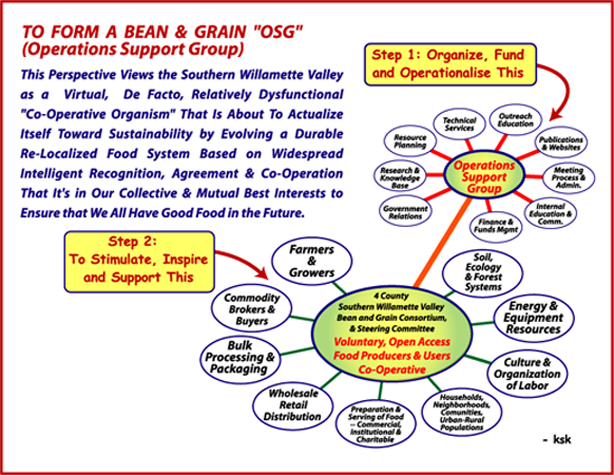

Scheme and Scope of Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project: The Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project is intent on no less than a ground-up rebuilding of the Willamette Valley food system. The first step is to encourage the conversion of significant portions of grass seed acreage to wheat and bean production and/or the incorporation of wheat and beans crops into grass seed producers' regular field rotations, with the underlying purpose of gradually growing many more food crops and increasing varieties of grains, legumes, and edible seeds in the valley. Also included in this process is an emphasis on sustainable agricultural practices, a critical part of which is a steady transition away from petrochemical inputs and into organic farming techniques.

After what has been an accelerating fifty-year run at the international grass seed market, the Willamette Valley is essentially two generations deep in grass seed farmers, many of whom are sixty years old or older. Knowledge for growing beans, grains, and other valuable food crops in the valley has been partially lost to changing agricultural philosophies and must be recovered. Part of the Bean and Grain Project’s mission is to both inventory regional agricultural knowledge and to experiment with growing techniques past and present. Appropriate crop rotations, conservation tillage techniques, use of organic inputs, non-chemical or limited-chemical weed and pest control, all of these concerns will be different for bean and grain production than they would be for grass seed. The technical aspects of tending the land for this kind of transition is critical and to some extent ground-breaking.

The effort to grow more grain and beans in the valley is aimed at local buying not the global market. As local food system infrastructure is lacking in the Willamette Valley, the Bean and Grain Project will also facilitate a rebuilding of the individual parts of the food system (processors, distribution hubs, storage facilities, and markets) in step with increased food production and diversity. A similar effort was needed in the early frontier settlements of western Oregon. As the valley attracted more and more settlers, all the various aspects of a food system were created as required–grain millers, grain silos, food markets, and distribution hubs. This will be a more difficult task now as it will be in direct competition with the existing global market and national franchises. Incentives for local buying will be linked to fresher foods, decreasing long distance transportation costs, and community building.

The value of community building is something that is often lost in the modern consumer mentality. Fundamental to any kind of food system rebuilding or relocalization is the understanding that social capital, the synergy of community, is more valuable than money and is not susceptible to market fluctuations. Recognizing this fact is absolutely critical to sustainable food security in a world we see changing before our eyes right now.

Step-by-step Project Implementation: As Harry MacCormack tells the story, he first began to think seriously about growing grains and beans in the Willamette Valley about three and a half years ago. He was shopping in Corvallis' First Alternative Food Coop when one of the members directed him to the store's bulk food bins and pointed out that none of the grains or beans came from local farmers. Always open to experiment, MacCormack bought small portions of sixteen items available in bulk that were sold as seeds and planted them on his farm. When all of them sprouted and began to grow, it got him thinking: What is the potential for growing grains and legumes in the Willamette Valley? As his "bulk food seed starts" took off in the hearty organic soil of Sunbow Farm, it became very obvious that the potential was great. Harry planted a small plot of black beans. At the end of the summer, he harvested and weighed the results. The numbers worked out. Black beans could be a competitive Willamette Valley crop.

The project took its first big step about six months later when Corvallis-area farmer Willow Coberly met Harry MacCormack at a lecture he gave on conventional versus organic farming practices. Coberly, who co-owns American Grass Seed Producers with her husband Harry Stalford, then took a workshop at MacCormack's Sunbow Farm and became convinced that organic farming could very well be the wave of the future in the Willamette Valley. Shortly afterward, she introduced her husband to MacCormack and from ensuing conversations, Coberly and Stalford agreed to convert one twelve-acre grass seed plot to organic and to prepare another 135-acre plot for transition to organic in order to test the viability of the grain and bean strategy.

The conversion of cropland farmed with petrochemical inputs to organic involves a three-year transition period. MacCormack and Shepard Smith, of Soil Smith Services, assisted Stalford and Coberly through the various stages of crop rotation and chemical mitigation procedures. A significant part of this process involved adding large quantities of compost tea to the soil to rebuild microbial and bacteria life in the otherwise dead, chemically overworked soil. Three years later, the first 12-acre plot was certified organic and ready to plant.

In conjunction with this work with Coberly and Stalford, MacCormack and Khrishna Khalsa, a community organizer, became involved in discussions with Robert Serrano, Vice President of Technical Services for Grain Millers in Eugene, and Richard Turanski, Founder and President of GloryBee Foods, a natural foods distributor in Eugene. The purpose of these discussions was to establish a connection for local growers with a large local grain processor and a local distributor. If the farmers were going to change what they grow and sell it in the Willamette Valley, they would need access to both.

In conjunction with this work with Coberly and Stalford, MacCormack and Khrishna Khalsa, a community organizer, became involved in discussions with Robert Serrano, Vice President of Technical Services for Grain Millers in Eugene, and Richard Turanski, Founder and President of GloryBee Foods, a natural foods distributor in Eugene. The purpose of these discussions was to establish a connection for local growers with a large local grain processor and a local distributor. If the farmers were going to change what they grow and sell it in the Willamette Valley, they would need access to both.

These early discussions created enough interest in all parties that the Lane County Food Policy Council hosted a meeting on January 14, 2008, titled Community Food Security, to introduce the Bean and Grain Project to the public. MacCormack, Serrano, and Turanski spoke to a group of about fifty people that included Harry Stalford, Willow Coberly, Denise Griewisch, Executive Director of Food for Lane County, several members of the Oregon State University Agriculture Department, a handful of local farmers, and many other interested community members. At the center of the discussion was concern for peak oil. As product transportation and petrochemical farm inputs are significant factors in food costs, oil prices and food security are closely linked. Converting grass seed acreage to acreage for beans or wheat would allow the south valley to grow more food closer to home. With petroleum prices already over $100 a barrel and wheat pushing $15 dollars a bushel, the gathering could easily feel both the urgency and beauty of the Bean and Grain Project. The meeting adjourned with a very positive response from those attending and received front page coverage the next morning in Eugene's daily newspaper, The Register-Guard.

Three months later, on April 4th, 2008, Harry MacCormack and Krishna Khalsa convened a gathering of twenty-two interested residents of the south Willamette Valley at Sunbow Farm for an open discussion of the Bean and Grain Project with a focus on the farmers needs and concerns. The group included six local farmers, two members of Oregon Tilth, a member of the USDA Farm Service, and several members of non-profit food groups. The intent of the meeting was to gather information about the transition of Willamette Valley farmers away from grass seed production into grains and beans. Of specific interest were the following questions: What is the current situation of Willamette Valley farmers and what are their needs in transitioning to organic beans and grain? What problems will the farmers face during this transition? What must the project organizers do to support the farmers during this transition? How can GIS mapping be used to facilitate the transition and best plan future cropland use? What are the next steps needed to accomplish the project's goals?

Both Willow Coberly and Harry Stalford attended the meeting. As early adopters of the bean and grain conversion, they provided some of the most important input to the meeting and prompted a vibrant farmer to farmer discussion regarding relevant farming practices, hurdles to clear, and an agenda of things that were simply as yet unclear. Though the discussion was often heated and negative, the rose-colored glasses were off and the needs and difficulties of the tasks ahead were clarified–with one very obvious conclusion underlined: every effort must be made to support and ensure the success of Coberly and Stalford's work. Stalford has been a successful grass seed farmer for many years and has considerable influence in the south Willamette Valley farm community. The test plots he had in the ground now must show the potential for economic success for the project to move ahead.

One result of the meeting was a laundry list of concerns that the farmers either were already facing or could expect to face in converting to organic beans or grains (see Appendix A). There was also a reaffirmation that the project needed to seek grants for funds to create a staff and to cover material expenses.

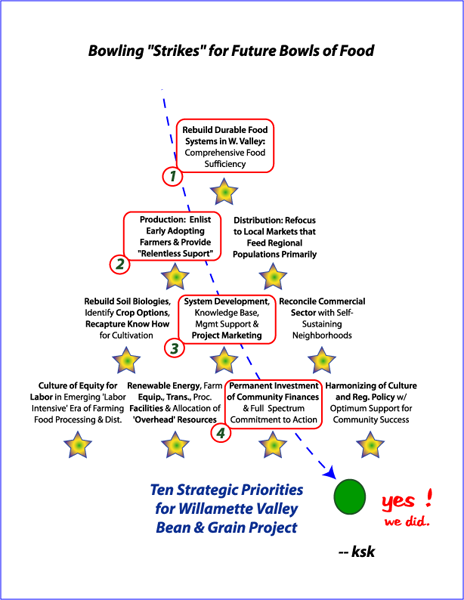

Three weeks after the April meeting at Sunbow Farm, the project organizers formed a group to develop a business model to facilitate targeting viable grants or private institutions for funding. This group met in May and June to discuss and create a business model appropriate to the project's purposes and goals. During that time, Harry MacCormack drew up a set of ten project design principles. These principles, listed below, delineate the intent, direction, and manner in which the Southern Willamette Bean and Grain Project would proceed and also provide the framework and goals for the project in general.

1. Encompasses four counties, including coastal and low cascade areas.

2. The project will be a large, co-operative effort of many small and medium sized producers (growers), processors, storage facilities, and distributors who are rooted in local communities, and organized to benefit the consumption of local products while supporting the efforts of everyone else involved. (We anticipate that larger producers (growers) would be partners with only small parts of their production, processing, etc, acting as a small independent unit from their larger industrial farming base.)

3. Use of a Cooperative Community Supported Agriculture model in which consumers contract with producers, placing one third of contract price up front (or some other percentage). Shared costs across the community can raise money to fund on-going, community held, 501 C5 organization which facilitates all interactions, organizing, moving contracted product, handling money, finding investors for cooperatively owned machines, buildings etc, and support for privately owned production tool etc, such as upgrades, needed repairs, etc.

4. Membership is contingent upon entering into product contracts, paying up-front one third or other contracted support fee, and participation at whatever level possible in the on-going, season to season, processes involved in insuring the development and production of locally-based beans, grains, and edible seeds.

5. Establish affiliation with Ten Rivers Food Web and Willamette Farm and Food Coalition which are 501 C3 corporations. Their joint fundraising and grant receiving capabilities should be used for bringing awareness to urban and rural communities regarding the needs, production intricacies, and organizational opportunities, particularly at neighborhood and small community levels, that can effectively build a locally-based food system. Education, assessment, and research are all functions that can be funded by a 501 C3 designation. Under education mentoring, interning and other types of information and skill sharing are refundable. The actual building of the business of networks of local food production to consumption and their day to day maintenance and operation are functions of the 501 C5 community held organization focused by a board of directors and run by managers whose purpose is clearly stated.

6. Transparency in fully reporting "means of [agricultural] production" should be stipulated and written into all agreements. If other than certified organic production methods are used, all inputs and methodologies should be agreed upon in contracts. Non-pollutive and biologically resilient methods should be a collective goal of the SWVBGP.

7. Product quality in terms of nutritional density should be routinely measured and recorded at all levels of production and distribution, as an essential basis for defining food quality, and to stimulate continual evolution and improvement of farming practices.

8. Decentralized production, processing, and distribution, and utilization of smaller acreage even within larger farm or production units should be a goal.

9. Organizing urban, rural, and other styles of community-end-users to fully participate in a season to season contractual food process is required for this community-based local food system/network to function.

10. Individual and community vitality is the ultimate goal of this project, within the context of biological resiliency. Investors become members of this project not so much for personal gain (especially financial gain) but as doing the work entailed in community-wide agreements leading to vitality and well-being. Building and maintaining a secure locally-based food system satisfies needs for prosperity and recognition.

Special thanks is extended to The Willamette Farm and Food Coalition and The Ten Rivers Food Web and Hummingbird Wholesale for their continued support of the Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project.