Home | Spaceship Earth | Book Reviews | Buy a Book | Bean and Grain Index | Short Stories | Contact | Mud Blog

2/29/2008

The foundation of any community is its food system. A region's capacity to produce, process, and distribute some significant portion of its own food has always been a measure of social and economic stability. As we face the unknowns of population pressure, peaking oil production, and climate change, securing local food resources will become one of our highest priorities.

Over the last thirty years, the globalization of the market place has expanded trade with a rich and diverse new array of products and product sources; however, it has been at the cost of regional economic balance, especially at the local level and especially for local food systems. We have out-sourced food processing to the global market much like we have out-sourced jobs. Due to vanishing local infrastructure even farm communities have lost the ability to feed themselves because they can't process what they grow. Oregon's Willamette Valley makes an ideal case study for both detailing the situation and articulating the strategy of relocalization as a way to alleviate the problems.

Relocalization is a community design principle aimed at reducing our carbon footprint. It's mass transit. It's walkable cities. It's shorter commuter distances. It's local processing of local resources. It's rebuilding local food systems. This design can be readily applied to agriculture in the Willamette Valley. Currently less than three percent of what the Willamette Valley populace eats comes from western Oregon, meaning ninety-seven percent of the valley's food is imported. Similar numbers apply across the board to just about any region of the United States, but with particular poignancy for the Willamette Valley.

The bioregion defined by the Willamette River watershed is one of the most bountiful in the Untied States. The Willamette Valley is a hundred mile long, two-million acre stretch of prime cropland bordered by a dense, eco-rich coniferous forest. The climate is mild; wet in the winter, dry in the summer. It is excellent for raising livestock and farming, with soil particularly suited for many types of grasses and legumes. There is tremendous flexibility in what can be grown and the way that the various field crops can be rotated for the health of the land. Home to a variety of fish and other wildlife, the Willamette River basin is essentially a garden valley, Oregon's own little piece of Eden.

Not that long ago, in the 1950s and 60s, Willamette Valley agriculture exemplified this, producing a wide array of grains, fruits, and vegetables. Wheat once represented almost a third of what was harvested. Barley, oats, snap peas, and sweet corn were also significant crops. Tomatoes, broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, potatoes, onions, cucumbers, peaches, raspberries, strawberries, hazelnuts, and squash fill out the mix. Fifty years ago, Willamette Valley farmers were providing about half of what the valley residents were eating. Though certainly there were items which did not grow in the valley and the population was about half of what it is today, the region did have the capacity to feed itself.

This agricultural picture of the Willamette Valley, however, has been turned inside out in the last twenty-five years. The dynamics of the global market place have centralized food distribution into large storage, processing, and transport conglomerates while delocalizing regional food systems throughout the world. Nearly everything we eat comes from some place else–often from over fifteen hundred miles away. Oregon farmers, like most farmers, tend to follow market lines. In the globalized economy, this means moving away from diversify and catering to specialized markets. In Iowa, for example, where there is the potential to grow all kinds of food products, corn and pork production dominate the large and mid-size farms and very little of what they produce stays home for Iowans. This may be the best way to maximize profit, but it tends away from local agricultural balance and, in a world where the price of fuel will only increase, away from economic stability and local food security.

The dynamics of this local/global reversal are well documented. The expansion of world markets, the liberalization of trade agreements, and the general globalization of the international economy have changed the way we buy and sell all things, but with no greater impact than on the way we buy and sell food. Labor costs, regional agricultural niches, and comparative advantage have turned states and small nations into one-dimensional economies. Whether it is coffee from Columbia, palm oil from Malaysia, or corn and pork from Iowa, the trend is to less regional diversification and more enhancement of special markets. Over the short run, this has resulted in higher profits. In the long run, however, lack of diversity in regional economies works against stability and sustainability.

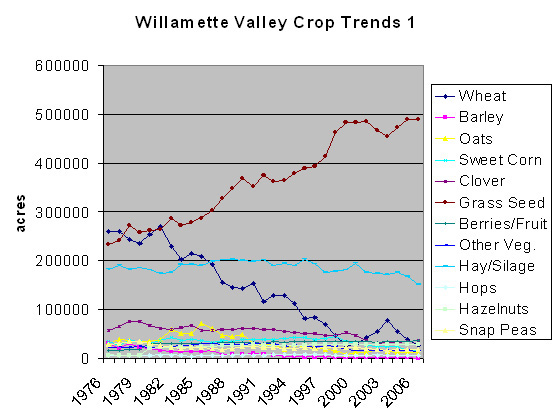

The graph above, "Willamette Valley Crop Trends 1", tracks all significant crops grown in the Willamette Valley by acreage over the last thirty years. On one hand this graph shows the incredible diversity of crops that can be grown in the Willamette Valley and the quantity that has been grown. On the other hand, it also clearly reveals the effect of the globalized market on Oregon agriculture. Beginning about 1983, as wheat prices eased off record highs, Willamette Valley farmers began a steady trade-off of wheat acreage for ornamental and forage grasses, that is, grass grown to produce grass seed which is then shipped all over the world for suburban lawns, golf courses, and pastures. Grass seed is now the valley's cash crop. Of the 900,000 acres of field crops in western Oregon in 2006, 500,000 acres of that was used for grass seed production. That's over sixty percent of all field crops. In the same year, less than 30,000 acres of wheat was grown in the valley.

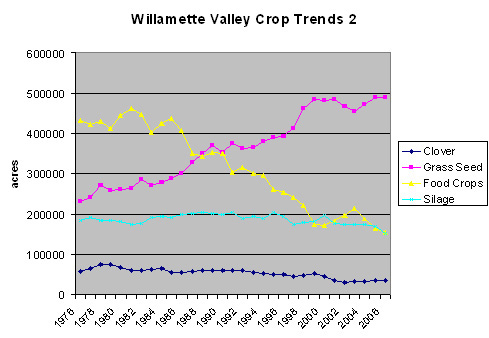

This means that more than half the field crop acreage in western Oregon in 2006 was for grass seed instead of food. "Willamette Valley Crop Trends 2" shows this graphically by combining all food crop acreage (fruits, vegetables, and grains) and mapping it against grass seed acreage. The divergence is hard to miss. Globalization has enabled specialized and long distant markets while at the same time diminishing food crop quantity and diversity at home. Common sense and concerns for food security would argue against this trend.

One reasonable response to this is relocalization. Though a current buzz word that suffers somewhat from overuse, relocalization is a management strategy designed to alleviate the impact of peak oil and climate change. It is based on the premise that condensing or localizing communities can minimize fossil fuel usage for transportation and thus carbon emissions. This strategy emphasizes buying locally grown food with the idea that simulating local farm production and markets reduces the need for long distance food transport.

This is not new by any means. Organizations like Lane County's Willamette Farm and Food Coalition, Food for Lane County, and the Helios Resource Network have been pushing local food buying for many years with just this intention–reversing the effects of globalization and bringing more stability to the local agricultural economy. Unfortunately, produce grown in countries where labor costs are significantly lower than in the United States can be cheaper to Oregonians than produce grown in the Willamette Valley–even with freight costs added in. This makes progress in establishing local food markets extremely difficult. In the last few years, however, peaking oil production and awareness for food security have added fuel to the relocalization fire. More than just the wisdom of a diverse and balanced agricultural economy, the labor advantage of food producers in distance countries will gradually be lost to freight costs as the price of fuel rises, and the local food movement will gather market force.

This is a start. But there is more to the story.

In addition to lost agricultural balance in the Willamette Valley, there has also been a gradual loss of food system infrastructure. Because we are receiving ninety-seven percent of our food from out of the region and because much of it is already packaged, grain millers, food processors, and local farm produce distribution hubs are also disappearing from the Willamette Valley, meaning not only does the region not grow its own food, but it also doesn't have the capacity to process or distribute what is grown. At a very basic level, we are losing the ability to feed ourselves. This is nonsense in a valley like ours.

At a deeper level, and no less important than what is grown, is how food is grown. In the last fifty years, industrial agriculture has concentrated on production and maximum yield. Petrochemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides have been used in enormous quantities to pump and protect yields. Like petroleum products in general, these carbon-based chemicals are getting more expensive and adding to the price of food, while at the same time negatively impacting the vitality of the soil and contaminating the ground water. This is a real problem in the Willamette Valley. Even with the valley's natural fertility, chemical-input farming is wearing out the soil and trailing toxins through the watershed. This form of agriculture must eventually give way to organic farming. Even should agriculture diversify, even should the local populace significantly increase locally food consumption, if production is based on petrochemical additives, it can not sustain. This is another critical part of insuring local food security.

Viewed through the lens of sustainability, Willamette Valley food systems show three major weaknesses. Less than twenty percent of what is grown here is food. Food processing, storage, and distribution infrastructure has all but disappeared, and the markets for selling local food are limited. Thus food system relocalization efforts in the valley must target how and what farmers grow, the rebuilding of food industry infrastructure, and creating more markets to link buyers, growers, and distributors. These same targets are applicable to almost any region in the United States.

The most direct way to zero in on these targets is to stimulate local food markets. As said before, this can be a slow and difficult process working against existing market price points, but there is reason to believe that this could change. Energy represents fifteen to twenty percent of the cost of food right now. As the price of petroleum rises, so will that percentage. Eventually transportation costs will leverage labor. The global food network will undergo a change, and local food markets will have the opportunity to gain priority.

In addition to the rising price of petroleum products, the grain market has also begun to change. Ethanol policy has turned great chunks of crop land into biofuel plantations, cutting into both wheat and corn-for-food harvests. Add extended drought in several parts of the world and a growing middle class in India and China and grain prices have been at record levels since 2008. It is true that the grain market is susceptible to fluctuations and has always been a difficult read for farmers, but grain consumption (mainly corn, wheat, barley, oats, rice) comprises more than half of what humans eat–and last checked our total population was still growing. Much like the petroleum market, there is evidence that the grain market has taken an historic turn. Peaks and valleys will occur but prices have reached a new plateau below which they are not likely to fall. This, even more than programs to promote local food buying, has already caused wheat acreage numbers in the Willamette Valley to climb and grass seed acreage to fall. Again, outside forces are pointing in the direction of more local food production.

Still we are talking about a transition that will require several years of sustained effort, and certain parts of it must be enabled at the ground level within the region. Yes, over time it is likely that the pocket book will help individual buyers on a day to day basis choose local. Market forces may also push farmers toward more diversity with each new growing season. But the biggest and slowest moving piece of the puzzle, rebuilding infrastructure and markets, will require a commitment from the business establishment and local government leaders. As current Federal farm bill legislation continues to work in favor of large food conglomerates and against its local competition, increased grass-roots engagement will be necessary to make any of this happen.

It should be noted that a fully local food economy is not the goal. That would be impossible. But local food buying whether by individuals, food markets, institutions, restaurants, or processors needs to be stimulated beyond today's three percent range to something more like twenty or twenty-five percent. This level of relocalized economic involvement could engender the kind of balance and stability that is needed to bring a modicum of food security to the populace and also a degree of sustainability to Willamette Valley agriculture.