What is food security?: There are many facets to food security. For the sake of this discussion, they will be grouped into immediate issues, long term trends, and systemic maintenance and are briefly defined below.

Food security's most immediate issue is to feed the less fortunate. This is what most people think of when the food security is mentioned. But there are also immediate concerns for safe food–meaning free of chemicals or disease causing bacteria–and healthy food–meaning nutritious and good for you. And then there is the ever present need to have food available for an emergency or a natural disaster.

Long-term food security trends include a changing climate–how will climate change affect water availability and the growing seasons, peaking oil production–how will rising energy prices affect the way we grow, process, and transport food, and the problematic demographics of farm ownership and farm labor–who will be our farmers and farm workers of the future?

Systemic maintenance addresses farming practices and food system viability. Clearly food security depends on farming practices that are sustainable over the long haul. This means using practices that conserve or improve the soil, protect the ground water and the environment in general, and produce food that does not contain chemical residues. Food security also depends on working local food systems, that is, having all the parts and pieces that get food from the farm to the dinner table–production, processing, storage, transportation, and markets.

Willamette Valley Agriculture–Then and Now: Our foodshed can be loosely defined as the Willamette River watershed or more simply the Willamette Valley. The valley is a hundred-mile long, two-million acre stretch of prime farmland bordered by a dense, eco-rich coniferous forest. The climate is relatively mild–wet in the winter, dry in the summer–and is ideal for farming and raising livestock of all kinds. The soil is fertile and particularly suited for many types of grasses and legumes. There is tremendous flexibility in what can be grown–more than two hundred edible crops–and the way that the various field crops can be rotated for the health of the land. Also home to a variety of fish and other wildlife, the Willamette Valley is a veritable garden paradise.

As recently as 1970, Willamette Valley farmers produced a wide array of grains, fruits, and vegetables. Wheat was the largest crop by acreage. Barley, oats, snap peas, and sweet corn were also significant crops. Tomatoes, broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, potatoes, onions, cucumbers, apples, peaches, raspberries, strawberries, hazelnuts, and squash fill out the mix. In the 1950s, the mid-valley was literally the world's most productive fruit and vegetable processing region in the world with as many as thirty canneries in the Salem area alone. Though there were certainly many items which did not grow in the valley and the population was about half of what it is today, the region did have a working food system, including grain storage and milling, and the populace was consuming in excess of fifty percent locally grown food.

This image of the Willamette Valley agriculture, however, has changed considerably in the last thirty years due to the evolution and maturation of the global marketplace. The expansion of world markets, the liberalization of trade agreements, and the general globalization of the international economy have changed the way we buy and sell all things, but with no greater impact than the way we buy and sell food. In no small way, labor costs and comparative advantage have more to say about how we tend the land than the land itself. Whether it is coffee from Columbia, palm oil from Malaysia, or corn and pork from Iowa, the trend has been to less regional diversity and increased focus on special markets and monoculture. Western Oregon has not been immune to this dynamic.

Increasingly since 1980, Willamette Valley farmers have turned to growing rye grass, bentgrass, and fescue to produce seed because they were the most profitable western Oregon field crops per acre on the global market. By 2005, nearly sixty percent of the cropland was planted with grass seed varieties, the number of local fruit and vegetable canneries had dropped from nearly fifty to less than five, grain storage and milling had all but disappeared, and the local populace was importing more than ninety-five percent of their food. What was once a well-balanced and diversified agricultural region with all the necessary infrastructure for a working food system had become the grass seed capital of the world, and one of the most fertile and well-balance agricultural regions in the United States could no longer feed itself.

Due to the recent economic downturn–now at eighteen months and counting–and vastly reduced housing starts, the Oregon grass seed industry has fallen on hard times and Willamette Valley agriculture is in the early throes of transition. Exactly where we are headed is still an unanswered question, but wheat acreage has increased substantially since 2008 and many grass seed farmers are looking for other alternatives. Perhaps there is no better time than the present to evaluate new directions with increased food security and self-reliance as our target.

Immediate Issues: Most of us are aware of concerns for world hunger, the 1.5 billion people who live on less than $1.50 a day and the 30,000 children that die of starvation daily, and yet it is not well know that Oregon's percentage of undernourished ranked second in the United States to Mississippi in 2009 at 4.5 percent. Even closer to home, a report published by Food for Lane County stated that 10,000 children in the county live below the federal poverty level and that a third of all those that received food boxes in 2009 were younger than 18 years-old. Similar statistics apply to all the counties in the Willamette Valley. While these numbers are certainly nothing like what we see in the developing world, they are especially disturbing for western Oregon because of our enormous potential for growing food.

The Willamette Valley, like all of the United States, is pretty much hard-wired into the global food system and, as mentioned before, we eat less than five percent locally grown food. This means we eat a lot of overly processed food, have only a general idea where our food comes from, have almost no idea how it was grown, and only in the rarest cases do we have any knowledge of the farmer who grew the food.

As is well publicized, obesity is a huge epidemic in the Unites States, and Oregon is no different. Recent statistics from the Center for Disease Control reveal that a quarter of all Oregonians are obese. This represents more than a doubling since 1995! Clearly there is work to be done here regarding safe and healthy food.

Our line of supply for food is essentially Interstate Five. Should an enduring ice storm or a runaway forest fire or some other kind of emergency stop traffic on the Interstate, because we have given over our local food system and food storage to the global market, we do not have large quantities of food on hand at a moment's notice. Our only source of food would be what is in our kitchen cupboards or on the shelves of our grocery store, about three days worth, meaning we would struggle badly if any kind of disruption lasted more than a week. At that point our populace would have to depend on federal emergency resources and, like New Orleans after Katrina, would be reliant on FEMA for assistance. This is shaky preparation at best.

Long-term Trends: Exactly what the Willamette Valley should expect with climate change is difficult to predict. In any case, a changing climate is a serious concern and could impact the availability of water, seasonal weather dynamics, and increase the number of catastrophic weather events–and emergency situations like those mentioned above.

While most scenarios for climate change in the Willamette Valley are not as disturbing as those for other parts of the United States, we might suffer for our good fortune rather than our misfortune. Should the American southwest get much drier than it already is, as is predicted, western Oregon would be a likely magnet for climate change refugees coming from the south. In other words, we might suddenly get a population influx that traditional population estimates for the Willamette Valley simply do not include–and this would be with a serious impact to our food security.

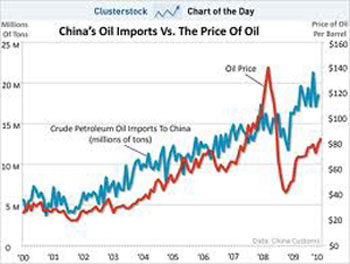

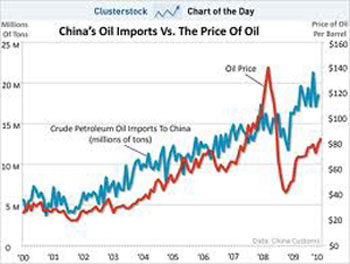

We rarely think about it, but our food supply is almost entirely dependent on fossil fuels and petrochemical inputs. Conventional farm production includes fertilizers made from natural gas, petrochemical herbicides, and petrochemical pesticides, and nearly all farms need diesel for their machinery. Once the food is grown–conventional or organic, there is again a need for diesel to transport it to processors or distributors, who then must secure their product in petroleum-based packaging before trucking it to grocery stores. The consumer must then drive to the store to buy it and bring it home to cook on his or her gas range or electric stove. Fifteen percent (and rising) of the cost of food today is energy related–energy to produce, energy to process, energy to transport, and energy to prepare.

The Willamette Valley can not expect to escape from the effects of peak oil. As part of the global food system, we rely on cheap fuel to freight in food at reasonable prices. Escalating petroleum prices would add to the cost of transport, production, and, down the line, to retail prices, while also adding pressure to our already stressed economic situation–thus more unemployed and homeless. This takes us back to food security's first concern–feeding the hungry.

Farm labor is arguably the most understated of the long-term food security issues. Currently the average age of a farmer in the Oregon is 56 years-old and the majority of their children do not intend to stay on the farm. Add that according to the United States Department of Agriculture seventy-five percent of U.S. farm labor is Hispanic and more than half of that is undocumented, and we have a problem brewing at two levels. Like the rest of the United States, western Oregon farmers have come to depend on undocumented workers for cheap farm labor, and considering the political turmoil around this issue, there is no immediate solution on the horizon. The question bears repeating: Who will be Oregon's farmers and farm workers of the future?

Systemic Maintenance: It is well documented that conventional industrial agriculture, that is, large-scale monoculture combined with chemical fertilizers and extensive irrigation systems, is not sustainable. Over the long term, it wears out the soil and introduces chemicals to our ground water. Minimizing chemical inputs and adding diversity to what we grow, especially food crops, must be our long-term strategy.

In the Willamette Valley, farming is still ninety-nine percent conventional by acreage and heavily reliant on petrochemical inputs. Despite a history of self-reliance, today we are but a cog in the global food system, focused on just a handful of crops. Grass seed is the number one by acreage. Wheat is on the increase, but after that we are talking very modest variety when weighted by acreage, and the sad truth is we are not really set up to feed ourselves.

In the last twenty-five years, we have seen local food systems throughout the United States gradually give way to the global system. It is a system managed and run by large multinational food distributors and processors and is based on long range transportation. This remarkable global system has brought us many new products from all over the world and created new markets to sell what we produce, but it has two critical flaws. It came into being during an age of cheap oil–which is rapidly drawing to a close, and it tends to the gradual dismantling of local food systems, because American consumers have come to rely so heavily on distant markets and long-range freight.

This dynamic is as true for the Willamette Valley as it has been for other farming regions in the United States. Currently, we have but a skeletal food system. We lack food storage, processing, and regional distribution systems. At the very least, our food security depends on rebuilding this food system and its infrastructure.

A Vision for the Future: Currently, food security in the Willamette Valley is entirely dependent on the global food system, government response to catastrophic events, undocumented Hispanic farm labor, and petroleum-based fuels and farm inputs. Every aspect of this is suspect for one reason or another. The key to increasing our future food security would be to create some level self-reliance. In the ideal, the future Willamette Valley agricultural model would be based on rebuilding our local food system and using sustainable farming practices to do it.

What would this look like? First we accept that grass seed production and seed production in general will always be part of Willamette Valley agriculture, but particularly in the case of grass seed, this should exist as part of a balanced program that prioritizes growing all the various food crops that the valley already has a track record of producing and answering to local food demand before selling on the global market. Because this would involve no less than a forty to fifty percent reduction of grass seed acreage, including a considerable portion of land that food crops can not be grown on, we would also need to incorporate other non-edible field crops like flax, hemp, and other oil seed crops that could be grown in the less fertile or wetter soils–again with a priority for local needs over global demand. It would also be necessary to grow a balanced variety of edible field crops on the more fertile farmland opened by reduced grass seed production. Wheat is already heading in this direction, but other dry-stored commodities would be important for diversity and proper crop rotation. Barley, oats, rye, millet, buckwheat, and a variety of dry-land beans would be key staples to add to the foundation of our rebuilt food system.

Along with this increased food production–and the clear necessity of having willing local buyers, we would need the infrastructure to support it. New grain mills and storage facilities would be located near the major population centers in the valley. Fruit and vegetable cleaning and sizing distribution hubs would also be needed in these same population areas, as well as value-added processing facilities. Infrastructure for local processing of hemp, flax, and other oil seeds would be a non-food related bonus to this reinvigorated relocalized economy.

In the end, the idea is not to go one hundred percent local. That is impossible. We are talking about a reasonable balance between imported and locally grown. Instead of importing ninety-five percent of our food, we should strive to reduce that to seventy or seventy-five percent, so that we are eating, perhaps, twenty-five percent locally grown and processed food. This is enough to have a complete and working food system.

With such a system in place, we would be answering nearly every facet of food security. A sizeable portion of our produce would come from farmers we could actually meet and talk to about their farming practices. We would have healthier food choices, with plenty of excess and gleaning opportunity for local food banks. With storage and distribution centers up and down the valley, food would be close at hand for diminished transport cost and also readily available in the case of an emergency. Though labor would remain a question our nation as a whole must face, rebuilding our food system would also come with the added benefit of stimulating economic development and manufacturing jobs in a sector based on one of our greatest and most sustainable, if managed property, natural resources–the farmland. This is a future we could all live with!