Home | Spaceship Earth | Book Reviews | Buy a Book | Bean and Grain Index | Short Stories | Contact | Mud Blog

By Dan Armstrong

Context: The Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project is a small group of farmers and local food system advocates focused on rebuilding the local food system and promoting food security in Oregon's Willamette Valley. The Project intends to achieve these goals by increasing the quantity and diversity of food crops that are grown in the south valley, evaluating deficiencies in the food system infrastructure, building buyer/seller relationships for locally grown food, incorporating the culture of community into the fabric of the food system, and compiling resources on organic and sustainable agricultural practices specific to the region. As the name of the project implies, central to the task is stimulating the cultivation and local marketing of organically grown beans and grains to provide a nutritionally dense foundation of staples for year-round food resources in the valley.

The background, historic necessity, and overall strategy of the Bean and Grain Project is detailed in Project Report One of this report. Project Report One also tracks the progress of the Bean and Grain Project during the first five months of 2008. For the most part, this time was spent publicizing the intentions and philosophy of the project through community meetings with farmers, food distributors, food processors, and others concerned about food security issues. These meetings invariably also included a meal of locally grown beans and grain–a sure way of lifting communication to a higher level.

Harry MacCormack, owner of Sunbow Farm outside Corvallis, Oregon, has provided much of the motivation and vision behind the Bean and Grain Project. He has been experimenting for three going on four years, growing varieties of beans and grains not historically found in the Willamette Valley. Working in close conjunction with Harry MacCormack is Willow Coberly, another Willamette Valley farmer. Willow and her husband Harry Stalford co-own American Grass Seed Producers, a large grass seed operation based in Tangent, Oregon. Due to Willow's interest in organic practices and her belief in the need for increased food production in the valley, Willow and her husband have opened up portions of their grass seed acreage to the cultivation of grains and beans. The food production portion of their 9000-acre farm operation is known as Stalford Seed Farms.

The work of the Bean and Grain Project is both ambitious in scope and somewhat controversial in application. As Harry MacCormack has written, "The beans and the red wheat are giant experiments which all the agricultural establishment have deemed impossible crops to be grown here as part of our local food shed. From my three years of experience, I would say that we haven't yet proven them wrong, but we are a long way toward doing so." In this sense, the Bean and Grain Project is an experiment in the rebuilding of a local food system, and there should be no minimization of the part played by the active farmers in this project, Harry MacCormack, Willow Coberly, and Harry Stalford. They have invested much energy and risk into what is really a cutting edge four-county (Lane, Linn, Benton, Lincoln) agricultural project.

But there was more going on than meetings and discussion. The seeds that had been planted in the spring at Sunbow Farm and Stalford Seed Farms were now well out of the ground. The hopes and plans of the Bean and Grain Project resided in the whim of the weather and the day-to-day monitoring of the crops. Much was still unknown as the growing season began and the next four months would become as much a learning experience as an effort to stimulate local grain and bean production and rebuild the local food system.

What was Planted: While the dialogue created by the Bean and Grain Project stimulated the planting of several other small experimental bean and grain plots in the valley, the project focused on the certified organic test plots at Sunbow Farm and the certified organic test plots and large transitional field trails at Stalford Seed Farms.

Sunbow Farm: Harry MacCormack planted thirty-nine test plots at Sunbow Farm, varying in size from three foot by eight foot to a quarter acre. Twenty-seven of these plots were dedicated to grains, including Canadian triticale, hard red wheat, perennial rye, and several breeds of soft white wheat, including some older heritage varieties he received from the Seed Ambassadors based in Eugene. In addition to the grains, he planted a quarter acre of test plots in black beans, pinto beans, green lentils, garbanzo beans, adzuki beans, hokido soy beans, and edamame soy beans. He also planted eighth-acre plots of quinoa, flax, sunflowers, buckwheat, and amaranth to explore the possibility of edible seed production in the valley.

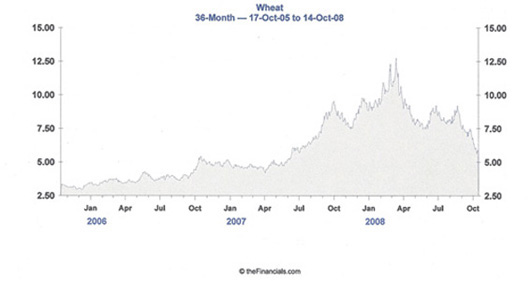

Stalford Seed Farms: Willow Coberly and Harry Stalford planted twenty-acre plots of garbanzo beans, red lentils, black beans, pinto beans, and anazasi-type beans. These were all third-year transitional, meaning the soil was being transitioned from conventional cultivation to organic. (The regular application of compost tea to the plots through three years hastened the usual six-year transition period, and these five, twenty-acre plots will be certified organic in 2009.) They also planted three certified organic plots: an acre-and-a-half of hard red wheat (using seeds from their 2007 test plot of red wheat); a quarter acre of triticale; and a eighth acre of soybeans. Along with these spring crops, Willow and Harry also converted 1200 acres of what had been grass seed acreage to conventional soft white winter wheat. Planted in October of 2007, this winter wheat acreage was as much a response to the global grain market as it was part of the Bean and Grain Project. Wheat prices spiked during the fourth quarter of 2007 and eventually surpassed the $15 a bushel mark in January of 2008. Many Willamette Valley farmers increased their winter wheat acreage in the fall of 2007 because of these market dynamics.

There are many different types of wheat. Winter wheat is planted in the fall and harvested in the early summer. Spring wheat is planted in the spring and harvested in the latter part of the summer. Winter and spring wheat is further classified as either white or red. Generally, the white wheat is soft with a high starch content and is used in pastry, pasta, and tortillas. Red wheat is hard with a high protein content and is used primarily in the making of bread. There are also hard white wheats and soft red wheats, but for the purposes of this report, the white wheat is soft wheat, and the red wheat is hard wheat.

White winter wheat production has been a significant part of the Willamette Valley for more than a hundred years but has been in steady decline, in terms of quantity, since record acreage levels (250,000 plus) in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 2006, less than 30,000 acres of winter wheat were planted in the valley. This was a record low and partly due to problems with "stripe rust" in the Foote breed of white wheat that was one of the commonly grown varieties in the valley (See Capital Press article). In the fall of 2007, winter wheat cultivation, prompted by the before mentioned rise in wheat prices, jumped to an estimated 120,000 acres, the largest amount in 12 years.

Hard red wheat has been grown in the Willamette Valley in the past, but it is generally not grown in the valley now and is not considered a viable crop, partly due to the lower yield of red wheat compared to white (30-50 bushels an acre versus 100-150 bushels per acre) and partly due to weather conditions. Harry MacCormack has been experimenting with hard red wheat at Sunbow Farm for three years now, and it was his work that prompted Willow Coberly to plant test plots at Stalford farms.

The Growing Season: A typically wet Willamette Valley April was followed by an unusually warm spell in May which was then followed by one of the coldest and wettest Junes in recent history. This was hard on the all the experimental bean crops, but especially the beans planted at Stalford Seed Farms. Willow Coberly and Harry Stalford received their seeds late and got them in the ground three weeks after they went in at Sunbow Farm; thus these plantings were not able to take full advantage of the warm weather in May.

At the June meeting of the project organizers, Harry MacCormack emphasized his concern about the weather and the fact that the effort to grow beans in the valley as a field crop did run contrary to conventional wisdom. Because a considerable part of the group's discussion centered on finding markets for the beans, the question of the crop's success made any type of planning and/or contract agreements with buyers particularly difficult. At this stage in the game, mid-June, no promises could be made about the bean harvest which would take place three months later.

July in the Willamette Valley was typically warm and growing conditions vastly improved, but the Stalford Seed Farms beans were well behind those at Sunbow Farm, and it still wasn't clear what the bean harvest would be and discussions with some of the larger buyers for both the grains and the beans stalled. Julie Tilt of Hummingbird Wholesale, and a member of the project group, however, remained positive and committed Hummingbird to buying as much of the local beans as she could. First Alternative Coop, a natural food store in Corvallis, was also still on board with the beans, and Krishna Khalsa, ever mindful of the part of community organization in localized movements, increasingly pushed the discussion to the potentials of neighborhood buying cooperatives. But the beans were still two months from harvest, and with the winter wheat nearing maturity, new concerns began to arise.

White Wheat Harvest: White winter wheat in the Willamette Valley was harvested during the second half of July and the first part of August. The 1200 acres of conventional white wheat planted at Stalford Seed Farms was a tremendous success, yielding between 135 and 150 bushels per acre and a total of almost nine million pounds of wheat. With the price of wheat at harvest in the $8.40-8.60 range, white wheat production proved to be a wise winter planting strategy in western Oregon, with a higher dollar per acre return than the production of grass seed.

(As long as wheat prices are above the $8.00 a bushel level, wheat stands to be a more profitable crop than grass seed, and there is little doubt many valley farmers have noticed this and will, more and more, consider making white wheat part of their winter crop rotation. With harvest complete, however, increased acreage throughout the United States has caused the price of wheat to drop, as it often does at this time of the year, and it is now (11/11) below $5.50 a bushel on the global market. This is nothing new to farmers. It is always very difficult to predict the market from the field, and farmers are invariably gambling from one season to the next with their crop selections, fully knowing high prices are likely to go down if too many farmers follow a trend.)

While the 2007-8 Willamette Valley winter wheat crop was a success, several critical infrastructure weaknesses were revealed at harvest and were cause for some problems and some lost crops. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, when wheat was selling at a good price, the valley harvested well in excess of 200,000 acres year after year. In the ensuing 20 years, however, a stable and low wheat price turned many valley farmers away from wheat and into grass seed production. The total annual wheat acreage steadily decreased to below the 100,000 acre level. During that time the infrastructure for handling large quantities of wheat was not maintained. In late July and early August of 2008, when the farmers began to harvest their wheat, this became obvious.

Global versus Local and Infrastructure Concerns: One of the core motives for the Bean and Grain Project is to turn our food system outside-in. Current food pathways in the United States are based almost entirely on the global market and the global food system. For increased food security and general economic balance, however, creating a local food system is a smart and common sense goal in these times of financial market instabilities, peaking oil production, and climate change uncertainties. Harry MacCormack emphasized this aspect of the Bean and Grain Project's intentions at a presentation in January, 2008 at GloryBee Foods: "The biggest part of the paradigm shift for all of us in this room to start thinking about is instead of growing food for export from this area, to start growing food for the area right here first, and then if we grow enough, we start thinking about Portland and Seattle, and then we start thinking about the rest of the world. And that's a huge, huge shift when we've been hooked into this global economy thing, for what twenty years now, where everything is flown everywhere because it's cheaper to do that way." In other words, it would be advantageous to change our priorities from the global market first (outside) to the local market first (inside).

In applying this philosophy to white wheat production in the Willamette Valley, the situation is not as clear cut as it is with the bean varieties that the project is trying to introduce to the local market. On one hand, any conversion of grass seed acreage to wheat acreage or, as is often the case, the addition of wheat into the grass seed rotation scheme is a move toward growing food instead of landscape ornamentals. In terms of global food security, this is a positive. When it comes to local markets, however, there is only so much demand for white wheat in the Willamette Valley. A rough estimate is that less than 10,000 acres could fill the entire valley's demand for white wheat–that is wheat for noodles, tortillas, or pastry. So regardless of the desire to stimulate consumption of locally grown products, the wheat market, more than any other part of the food system, because of its widespread use and its capacity to be stored and shipped, is almost entirely a global market and has been that way for a hundred years. This means some very high percentage (ninety-eight plus) of the wheat grown in the Willamette Valley was destined for shipment overseas.

This leads back to the infrastructure problems.

When the valley wheat farmers began what would be three weeks of harvesting in the second half of July, the freshly harvested wheat was trucked north to the Port of Portland to be bought by international grain buyer and distributor CLD (Cargill & Louis Dreyfus) and loaded onto freighters headed for Asia. As there had not been any significant wheat deliveries from the Willamette Valley in several years, the CLD terminal at the Port of Portland was not completely prepared for the sudden rush of Willamette Valley wheat farmers eager for a return on their crop. What had once been four wheat depots had been reduced to one, and CLD couldn't adequately handle the traffic. In the first week of harvest, trucks laden with golden wheat were backed up in slow moving lines waiting as long as six to eight hours to unload. In the second week of harvest, the port went to double shifts to relieve the pressure and a second company, Portland Grain, opened its depot to wheat. In the third week, it rained and harvest was slowed and the truck traffic gradually diminished to a trickle.

The Port of Portland situation, which was really only a problem during the initial weeks of harvest, was complicated by two other factors. The first factor was transportation. In the first two weeks, there was a shortage of available trucks to take the wheat to Portland. Truck scheduling got very tight and was further aggravated by the long lines at the Port of Portland. In some cases, wheat that was ready to go had to be left in the field or temporarily stored. The fact that the railroad, the most efficient way to transport large quantities of freight, played only a very small part in wheat delivery provided yet another insight into the situation. Again, however, as the press of the harvest diminished the transportation problem eased.

The second factor was storage. This was something the Bean and Grain Project group had discussed and worried about from the very beginning, but as a small volunteer group had little capacity to change. The valley had down-sized the wheat production infrastructure during the last twenty years and wheat storage facilities were greatly reduced, especially large privately operated elevators. There was some modest capacity for on-farm storage, and several grass seed dealers made what had been grass seed storage space available to wheat–but this was not nearly enough and temporary at best. While some growers were able to store portions of their wheat–Stalford Seed Farms was one of these, other farmers, struggling against the traffic buildup in Portland and the tight trucking schedule, simply left their harvested wheat in the field. This can work as temporary storage and is widely practiced in many parts of the United States. Yet when three days of rain began in the second week of August, a fair quantity of that wheat was damaged.

The situation was not dire in any large sense, but it was frustrating to the farmers, especially those who had not grown wheat before, and it made for a tense three weeks of harvest. In the end, it was an important heads-up on the condition of the existing infrastructure and may yet prompt a needed increase in wheat storage facilities in the valley and perhaps a reappraisal of the railroad freight system.

While local grain storage is clearly a vital part of any regional food system, one alternative to storing wheat on a farm or at a local elevator is selling the wheat at harvest as a futures option. The farmer can take his wheat to the shipping dock and, as a hedge against the market, sell it to the distributor on an open-ended futures contract. The farmer doesn't take payment on his delivery or set a price on his product until he or she chooses to do so. That is, the farmer plays the wheat market as long as he or she dares, paying four to five cents a bushel per month for this service. This is essentially a form of "cyber-storage," and in the volatile conditions of the current grain market a viable gamble. Wheat may have sold at $8.50 a bushel in August. It may be at $5.25 today. But it could easily be $10 or $12 or more a bushel by February–or less than $5.00. Welcome to the farmers' casino!

Red Wheat Harvest at Stalford Seed Farms: In addition to the large crop of conventional white winter wheat, Stalford Seed Farms planted an acre and a half of organic hard red wheat in the spring of 2008. As stated eariler, red wheat has generally not been grown in the valley in recent years, but because of Harry MacCormack's on-going experiments with red wheat at Sunbow Farm and the high value of organic red wheat, Willow Coberly and Harry Stalford did try a small plot in 2007. The results were not promising, but using the acclimated seeds from 2007, they tried again in 2008. This crop turned out much better, yielding 40 bushels per acre and producing about 3,000 pounds of hard red wheat. After reserving a portion of this for next year's seed, the remainder sold very quickly at Corvallis' First Alternative Coop and through direct farm sales via the Ten Rivers Food Web listserv and private email orders. This may have been one of the nicest results of the 2008 growing season and will likely result in an expansion of the organic red wheat crop at Stalford Seed Farms to 20 acres or more.

Wheat and other Grains at Sunbow Farm: Harry MacCormack's twenty-seven test plots of grain included rye, Canadian triticale, hard red wheat, and several varieties of white wheat. The majority of these grains grew well and produced quality product. One white variety showed the capacity to yield more than 150 bushels per acre. In general, however, Sunbow Farm's grain production was directed at a different question than that at Stalford Seed Farms. Harry wanted to see what kind of success a small homestead farm could have with grains that are traditionally grown as large field crops. His findings suggest there is quite a lot of manual labor involved in cultivating small plots of grain that is minimized by the large equipment on a farm of scale and that it is a bit of stretch to make grains a seriously profitable crop on a small scale, but that it is still a very viable crop as a source of homestead staples. "A small farmer can make a slim profit per acre before cleaning and bagging if grain is sold by the pound," Harry writes in his 2008 financial summary (see full document as PDF). "At 50 cents per pound the profit would be $397 per acre. At $10 per bushel the loss would be $403 dollars per acre." In times of increasing petroleum costs, the meaning of growing grain without petrochemical inputs or diesel-powered equipment is important, especially for plain and ordinary survival, something that is also an integral part of the Bean and Grain Project's concerns.

Bean Harvest at Sunbow Farm: The bean crop, which was one of the central focuses of the Bean and Grain Project in 2008 because it is such a good fit for the local markets, was harvested in September. Despite the cold June, the bean plots at Sunbow were reasonably successful, though not quite as productive as the test plots Harry grew in 2007. The green lentils, garbanzo beans, black beans, and pinto beans produced a yield of about 2,000 pounds per acre, down about ten percent from the previous year.

Sunbow Farm's test plots of adzuki beans, hokido soy beans, and edamame soy beans performed only marginally, and Harry suggests growing them only as novelty crops.

After three years of growing beans at Sunbow Farm, Harry summarizes his experience as follows: "Dry beans can be grown in the Willamette Valley. They are however a big gamble, especially when machine harvested. We would highly recommend that they be grown on smaller acreage where hand labor can offset some of the costs and risks. Small combines such as our JD 40 or an All Crop, if properly adjusted, should allow for larger dry bean acreage. Alternatively, without money to invest, substantial pounds of dry beans can be grown using simple tools and hand harvesting. In a post cheap petroleum future, this might be a necessity for many people. Markets are apparently there. We had no trouble selling our crop. In fact, we had way more orders than beans."

Harry MacCormack's Field Report 2008: For more detail on what was planted at Sunbow Farm, seed varities, nutritional information, processing, and financial considerations read Harry MacCormack's Bean, Grain, Edible Seed Research 2008 Report.

Bean Harvest at Stalford Seed Farms: Stalford Seed Farms grew 20 acres plots of black beans, pinto beans, garbanzo beans, red lentils, and anazasi-type beans. As stated above, these plots were all third-year transitional, meaning that next year these plots will be certified organic. Despite the fact that the beans went in three weeks later at Stalford Seed Farms than at Sunbow and that the weather in June was unusually cold, the black, anazasi-type, garbanzo, and pinto beans did produce fair crops. As these were all new crops at Stalford Seed Farms, there was a bit of a learning curve involved, however, in their cultivation and their harvesting. As a result, the late planting didn't give all the beans a change to ripen, and there was some difficulty in finding the right harvesting techniques for the short bean plants. Only the garbanzo beans fully ripened. They netted a sizeable return, 14,000 pounds, which, as Willow Coberly commented, could have been twice that with more experience in harvesting. Willow, however, was satisfied enough with the results of all four of these bean crops to want to repeat the process again next spring–with the advantage of one year's experience. All the beans Stalford Seed Farms produced sold quickly to local buyers, Hummingbird Wholesale, First Alternative Coop, and citizens buying directly from Stalford Seed Farms through the Ten Rivers Food Web listserv and email orders. In the end, much like the organic red wheat, demand outstripped production.

The red lentils did not fair as well as the other beans. Again it was a learning curve problem and the late planting didn't help, but as Harry's lentils grew well, Willow anticipates a considerably more successful crop the second time around.

Community Building: Including food security in the culture of community is fundamental to the rebuilding of a food system. Food security's last line of defense, especially in times of crisis or for the less fortunate, is often at the neighborhood level. When Federal food assistance programs or local food banks are insufficient, local communities, when fully incorporated into the food system or operating as their own system, have the potential to provide. The creation of neighborhood buying cooperatives, neighborhood staple storage, community gardens, regular community meals, and neighborhood incubator kitchens are key pieces to achieving that potential.

While the crops were in the field growing and during the time of their sale and distribution, considerable effort, primarily on the part of project member Krishna Khalsa, was put into generating community awareness for the project and what it could mean to this less talked about concept of neighborhood food systems. Krishna regularly put together "food generosity events" in Eugene, providing gourmet quality bean and grain dining both for neighborhood gatherings and the homeless. These events answered to the immediate needs of the less fortunate, created the genuine spirit of community that is so evident when food is shared together, and prepared the foundation for building neighborhood food systems.

This underlines an absolutely essential facet of the Bean and Grain Project; the synergy of community, the social capital of people working together, is more powerful than money. This is a message that is generally lost in our modern consumer society and overlooked as the added-value of buying locally grown products. The sense of community must be the glue that holds us together in times of uncertainty.

Lessons Learned: There is probably no better way to learn than by testing the waters. After two years of preliminary work at Sunbow Farm and Stalford Seed Farms, the 2008 growing season added another layer of confidence to the premise that several varieties of beans can be grown in the Willamette Valley that were generally not considered viable. The same is true for several varieties of grains, particularly the hard red wheat. It is already common knowledge that a wide variety of fruits, nuts, and vegetables can be grown in the valley, but the addition of staples like beans and grains to the local food system can not be undervalued. Increased crop diversity is extremely important to food security and local diet variety.

Education, as addressed in the April meeting at Sunbow Farm, is critical. As was seen this year with the beans at Stalford Seed Farms, the potential is surely there, but all the beans were first time field trials at Stalford Seed Farms and harvest is likely to be several times more productive as experience increases.

Similarly, education was a big part of the 2008 experience for the project organizers, especially regarding what is possible in the building of local markets and distribution systems for Willamette Valley beans and grains. The hoped for connection with Grain Millers and GloryBee Foods is still at least a year or more off, but the interest of smaller buyers like Hummingbird Wholesale, First Alternative Coop, the Ten Rivers Food Web listserv, and other neighborhood buying coops was tremendously encouraging. One neighborhood group in Eugene bought 2,300 pounds of garbanzo beans. In the end, the 2008 harvest could not meet local demand, and if early returns on 2009 orders for Hummingbird Wholesale are any indication, that demand will only increase.

1. There was success with many of the experimental crops. Black beans, garbanzo beans, pinto beans, anazasi-type beans, and lentils did well enough to continue with the process. Experiments with soy beans and amaranth were not so successful. The organic red wheat trials were the prize of the growing season and their acreage will be increased.

2. The early growing season in Willamette Valley can be difficult for beans. June was unusually cold in 2008 and can often be an unpredictable month in the maritime climate of western Oregon.

3. The timing of the bean plantings was critical. The Stalford Seed Farms' beans went in three weeks after those at Sunbow, and they could have used the extra time in the ground. Lentils involve somewhat different planting techniques than the other beans and these techniques needs to be improved.

5. The white wheat harvest revealed real infrastructure limitations, particularly storage, but also in transportation and the management of outgoing grain operations at the Port of Portland. In general, however, the white wheat, as a market play, was a solid success.

6. There are opportunities to hedge on wheat sales through future options. This can also be a form of "cyber-storage."

7. The part played by Hummingbird Wholesale and potential small markets, particularly neighborhood buying cooperatives and the Ten River Food Web listserv, was encouraging. Demand outstripped supply.

8. Large buyers are still reluctant to fully engage in contracting for local grains and beans. Continued success in the field and with sales to smaller buyers are the best ways to gather the interest and support of larger buyers.

9. Grain production is possible on small homestead farms, but tasks that involve machinery need to be refined and are often best done by hand. This makes grain harvesting and cleaning highly labor intensive. The same, to a lesser extent, is also true for the beans.

10. Harry MacCormack's field report 2008: Bean, Grain, Edible Seed Research 2008 Report.

11. Ten Rivers Food Web final report on Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project: Local Foods Project Final Report.

12. Final crop statisitcs–varieties grown, acreage, and yields: 2008 Crops and Yields.

Review of Initial Concerns (Six months later): When the Bean and Grain Project convened in April at Sunbow Farm with several farmers and local food system advocates, a list of concerns was created as part of one of the project's working documents. It is worthwhile to review these concerns and comment on them now that 2008 growing season is over. See Appendix B.

Next Steps: One growing season has passed; another begins. The seeds for the winter wheat crop are already in the ground. The same could be said of the Southern Willamette Bean and Grain Project. Organizational meetings, assessment of the past year, dialogues with farmers, processors, distributors, and neighborhood organizers, all of the same kind of activities that took place in 2008 will be revisited in 2009, yet with another year of experience and insight, a gathering ground swell of local support, and more acreage of beans and grains planted. A presentation to review this past year and attract more producer interest in 2009 will take place on January 20th (1:00 pm to 4:00 pm) in the Lane County Extension Service Auditorium at 950 West 13th Street in Eugene. See Announcement.

Special thanks is extended to The Willamette Farm and Food Coalition and The Ten Rivers Food Web and Hummingbird Wholesale for their continued support of the Southern Willamette Valley Bean and Grain Project.